by A. G. Noorani*

*The author is an eminent Indian scholar an expert on constitutional issues.

Abstract

Mohammed Ali Jinnah and Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi were masterful persons. For nearly a decade before the establishment of Pakistan, the Gandhi-Jinnah political duel was at the centre of political discourse in the subcontinent… In the case of the top leaders, idolatry in one country is matched by hate in another… This article is not an exercise in debunking. It seeks, instead to highlight some crucial encounters between the two which reflect their personalities, and their disagreements and agreements – Author.

Mohammed Ali Jinnah and Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi were masterful persons. For nearly a decade before the establishment of Pakistan, the Gandhi-Jinnah political duel was at the centre of political discourse in the subcontinent. That was entirely of Gandhi’s doing. Sturdily independent, Jinnah cared not a farthing for personalities. His concern was with policies, solutions and strategy. Court historians sprouted up in both countries, Pakistan and India, to please the public. Scholarship has suffered. It is concerned with the pursuit of truth; not the spread of nationalistic propaganda. The harm has been done. Myths were spawned by Authors; especially of the foreign variety. One called Jinnah a Managing Director of Tatas which would have disqualified him from practise as a barrister. He also called Zulfikar Ali Bhutto a Sufi. That charming epitome of grace Begum Liaquat Ali Khan, an Indian Christian, he called an Iranian beauty though he had stayed in her house off and on for nearly a quarter century. His name is Stanley Wolpert. Happy at his criticisms of Pakistan and its leaders, Indians, official and others of the elite, embraced him when he came to do a biography of Nehru. No one talks about him anymore.

In the case of the top leaders, idolatry in one country is matched by hate in another. Things began to change lately. S. K. Majumdar blazed the trail with his book Jinnah & Gandhi (M. L. Mukhopadhyaya, Calcutta 1966). There followed Gandhi vs. Jinnah by Allan Hayes Meriam, (Minerva Associates, Calcutta, 1980); Jinnah and Gandhi: Their Role inIndia’s Quest for Freedom by S.K. Majumdar (M.L. Mukhopadhyaya,Calcutta); and H. M. Seervai’s Partition of India : legend and Reality, (Oxford University Press, Karachi).

This article is not an exercise in debunking. It seeks, instead to highlight some crucial encounters between the two which reflect their personalities, and their disagreements and agreements. It is not widely known that Jinnah began his career with his maiden speech at the Imperial Legislative Council in support of Gandhi and a clash with the Chairman, the Viceroy Lord Minto.

A debate on the Resolution on Indentured Labour for Natal came up on 25 February 1910. The following is the extract from the proceedings: The Hon. Mr. M.A. Jinnah: “My Lord, I beg to support the Resolution that has been placed before the Council. The Hon’ble the mover put the question before the Council so clearly and concisely that there is very little left for anyone else to say. But the importance of this question requires that at least some of us should say a few words and express our feelings on this Resolution. If I may say at the outset, it is a most painful question – a question which has roused the feelings of all classes in this country to the highest pitch of indignation and horror at the harsh and cruel treatment that is meted out to Indians in South Africa.”

His Excellency the President (Lord Minto): “I must call the Hon’ble gentleman to order. I think that is rather too strong a word, ‘cruelty.’ The Hon’ble Member must remember that he is talking of a friendly part of the Empire, and he must really adapt his language to the circumstances.”

The Hon. Mr. M.A. Jinnah: “Well, my Lord, I should feel inclined to use much stronger language, but I am fully aware of the constitution of this Council, and I do not wish to trespass for one single moment, but I do say this, that the treatment that is meted out to Indians is the harshest which can possibly be imagined, and, as I said before, the feeling in this country is unanimous.” (M.H. Syed, Mohammed Ali Jinnah; Shaikh Muhammad Ashraf, Lahore; 1945).

Minto perhaps did not know that in 1907 Jinnah had been to England to press the cause of Indians in South Africa. He was 31 then. At the Anjuman-i-Islam Hall, Bombay, Jinnah delivered a lecture on “The Indians in Transvaal” before a largely attended meeting. His Highness, the Aga Khan presiding.

Jinnah referred to the Asiatic Law Amendment Act and the Immigration Restriction Bill and described the hardships entailed upon the Indians residing in Transvaal. He considered both these measures were scandalous pieces of legislation which affected the people of this country, and urged that various Indian communities should join in protesting against them, and asked the Government of India to do all it could to get them repealed. He said these were pieces of differential legislation. The Anti-Asiatic Act was passed in 1885, but owing to the great influence which was brought to bear by the British ministers upon the late Boer Government the latter were afraid of enforcing it. It was practically a dead-letter until after the recent war, when as soon as Constitution was granted to that Colony, it was revived. It was curious that ill-treatment of the Indians was made one of the reasons for declaring war against Transvaal and when the colony was annexed to the British dominions and a Constitution was granted to it, an Act which was ten times worse than the old Act was brought into existence. “… Let them have an Act in this country on the same lines which should exclude all the Colonials – all subjects of such of the Colonies as had Acts to exclude the Indians from their shores – from admission into this country. This was but the barest justice that could be done to India and Indians. They asked for redress, but failing redress they asked for retaliation.” (S.S. Pirzada; The Collected Works of Quaide-Azam Mohammed Ali Jinnah; East and West Publishing Co., Karachi,1984; Vol. 1, p. 5).

There was the reception of the Gurjar Sabha on 14 January 1918 in honour of Gandhi at which Jinnah presided and spoke of him in high praise (ibid. p.123). It is not widely known that Jinnah spoke Gujarati and Cutchi flawlessly.

The shock, but still not the breach came when Gandhi captured the Home Rule League and changed its character in breach of a solemn promise. Jinnah accepted his membership despite M. R. Jayakar’s warning. This episode has not received the notice it deserves; a Mahatmaric breach of promise. Before this he wrote to Jinnah on 4 July 1918: “I do wish you would make an emphatic declaration regarding recruitment. Can you not see that if every Home Rule Leaguer became a potent recruiting agency whilst at the same time fighting for constitutional rights we should ensure the passing of the Congress – League scheme, with only such modifications, if any, that we may agree to? We would then speak far more effectively than do today. ‘Seek ye first the recruiting office and everything will be added unto you.’ We must give the lead to the people and not think how the people will take what we say”. Later Gandhi managed to take over the Home Rule League and, in breach of his promise, changed its objectives. Along with Jinnah, M. R.Jayakar, Jamnadas Dwarkadas, Kanji Dwarkads, K. M. Munshi, R.G. Munsif, M. K. Azad, Morarji Kamdar, Jamnadas Metha, Hansraj Pragji Thackersey, Hiralal Nanavaty, Nagindas Master, Gulabchand Deochand, Chotubhai Vakil, Mangladas Pakvasa, Chandrashankar Pandya, N.B. Vibhakar, Manilal Nanavaty, and Y.M. Pakwasa resigned. (Quaide-Azam Jinnah’s correspondence, p. 82) Gandhi believed in quick fixes and went from one extreme (pro-British, here) to another. (For details view A.G. Noorani, Jinnah and Tilak, Oxford University Press, Karachi, pp. 43-58).

Shortly before that Gandhi wrote to Jinnah and others on 20 October 1920 offering him a “new life”. Jinnah in reply, recalled the events of the past.

Jinnah added: “I thank you for your kind suggestion offering me ‘to take my share in the new life that has opened up before the country.’ If by ‘new life’ you mean your methods and your programme, I am afraid I cannot accept them; for I am fully convinced that it must lead to disaster. But the actual new life that has opened up before the country is that we are faced with a Government that pays no heed to the grievances, feelings and sentiments of the people; that our own countrymen are divided; the Moderate Party is still going wrong; that your methods have already caused split and division in almost every institution that you have approached hitherto, and in the public life of the country not only amongst Hindus and Muslims but between Hindus and Hindus and Muslims and Muslims and even between fathers and sons; people generally are desperate all over the country and your extreme programme has for the moment struck the imagination mostly of the inexperience youth and the ignorant and the illiterate. All this means complete disorganisation and chaos. What the consequence of this may be, I shudder to contemplate; but I, for one, am convinced that the present policy of the Government is the primary cause of it all and unless that cause is removed, the effects must continue. I have no voice or power to remove the cause; but at the same time I do not wish my countrymen to be dragged to the brink of a precipice in order to be shattered. The only way for the Nationalists is to unite and work for a programme which is universally acceptable for the early attainment of complete responsible government. Such a programme cannot be dictated by any single individual, but must have the approval and support of all the prominent Nationalist leaders in the country; and to achieve this end I am sure my colleagues and myself shall continue to work.” (Vol. I; p. 400). This is perhaps the most elegantly worded letter in Indian politics.

Neither the Home Rule League take over nor the insults at Nagpur embittered Jinnah. He said at a condolence meeting on his friend C.K. Gokhale’s death in Bombay on 19 February 1921: “Having for its programme destructive methods which did not take account of human nature and human feelings, non-violent non-co-operation will be a miracle if accomplished. He said, before that it was not a political programme though it had for its object the political goal of the country. Such principles and doctrines as were preached and propagated by Mr. Gandhi, were opposed to the nature of an ordinary mortal like himself. Not one in a million could carry out Mr. Gandhi’s doctrine which has its sole arbitrator his conscience. The speaker could not contemplate how long the non-violent non-co-operation could last if all the boys were withdrawn from schools and colleges without substituting them by national schools and colleges. He still hoped the Government would think less of Mr. Gandhi’s programme and think more of what the intellectual opinion of the country felt, and he trusted that it would not be very long before a real change of policy as enacted so as to allay and satisfy the feelings of the people who were in entire accord with the spirit of Mr. Gandhi’s movement which, however defective, may be picked up and directed in a channel which might make the Government and administration of the country impossible. …

“There were now two effective ways of attaining their goal. The first was to put their hands in the pocket and pay for their country and the second was to shed their blood. As a matter of fact they were powerless. Now the only strength and effective strength was money… He (Gandhi) could have by all means started national schools and colleges and fill them up. There was a large percentage of boys who did not attend schools and he could have filled them up with those boys or he could have withdrawn the school-going boys from the schools and put them in the national ones, but he (speaker) did not like that boys should be withdrawn from the schools and thrown in the streets.

Concluding, Jinnah said undoubtedly Mr. Gandhi was a great man and he had more regard for him than anybody else. But he did not believe in his programme and he could not support it. He might stand out alone but he would say that in his opinion if the movement were directed in a right channel there was great hope. He did not know what Gokhale would have said or done now but he thought Gokhale would not have endorsed this programme had he been spared to live till now.” (ibid., Vol;1; pp. 410-411).

Meriam’s book records their continued cooperation. On 20 November 1922, Gandhi met Jinnah in Bombay and they agreed on a Resolution condemning British criminal practices which included power to arrest persons without a trial or even a statement of reason for the arrest. During the winter of 1924-25, both Gandhi and Jinnah worked at sessions of the All-Parties Conference seeking ways to issue communal harmony, but nothing tangible resulted from the Conference. Their paths crossed again on 2 November 1927, when both went to the Viceroy’s house to receive news of Royal Commission appoints.

Gandhi and Jinnah met several times in 1929. In August they conferred privately over the communal question. Two months later, Viceroy Irwin announced British acceptance of a Round-Table Conference and hinted at eventual Dominion status for India. On 12 December, Jinnah travelled to Gandhi’s ashram (retreat) at Sabarmati to discuss the Viceroy’s vagueness concerning Independence. On 23 December, both men met with Viceroy Irwin in Delhi concerning the Round-Table Conference and release of political prisoners. Saiyid reported that “perfect cordiality prevailed throughout the interview.” (pp. 47-48).

As late as on 3 December 1928 Jinnah wrote to the Viceroy Lord Irwin “I left with the impression that Mr. Gandhi himself is reasonable” (Waheed Ahmad, Jinnah-Irwin Correspondence, p.30).

A suppressed breach occurred at the Round-Table Conference in London when Gandhi offered a favourable settlement to Muslims if they supported him against the Scheduled Castes (untouchables). Dr. B. R. Ambedkar exposed it and published its full text in his book WhatGandhi and the Congress have done to the Untouchables (Thacker,1946).

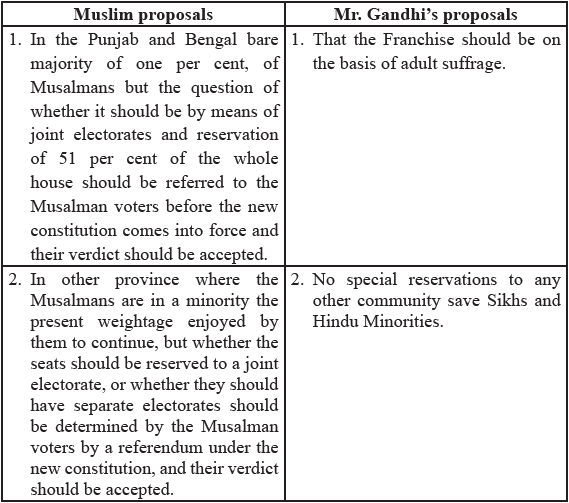

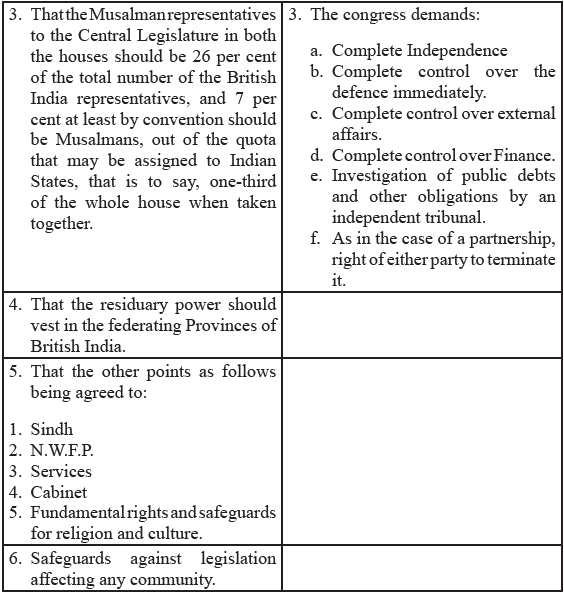

Mr. Gandhi planned to buy out the Musalmans by giving to the Musalmans their 14 demands, which Mr. Gandhi was not in the beginning prepared to agree. When Mr. Gandhi found the Musalmans were lending their support to the Untouchables he agreed to them their 14 points on condition that they withdrew their support from the Untouchables. The agreement was actually drafted. The text of it is given below:-

“DRAFT OF GANDHI-MUSLIM PACT

MUSLIM DELEGATION TO THE ROUND TABLE CONFERENCE.

Tel.: VICTORIA 2360 Queen’s House,

Telegrams: “COURTLIKE” 57, Sir James’ Court,

LONDON Buckingham Gate, London, S.W.1.

6th October 1931.

The following proposals were discussed by Mr. Gandhi and the Muslim Delegation at 10 p.m. last night. They are divided into two parts – The proposals made by the Muslims for safeguarding their rights and the proposals made by Mr. Gandhi regarding the Congress policy. They are given herewith as approved by Mr. Gandhi, and Muslim Delegation for their opinion.

Ambedkar explained:

- Stands for separation of Sindh.

- Stands for Provincial Autonomy and Responsible Government for the W.F. Province.

- Stands for Representation in Services.

- Stands for Representation in the Cabinet.

Significantly Jinnah’s reaction was to retire in London. On his return to India, he sought a Congress-Muslim League United Front against the British and fought the 1937 general election on a progressive manifesto.

Nehru had developed a phobia against Jinnah. Nehru and Azad rejected Jinnah’s offer of power sharing.

The breach occurred in 1938. By then the Congress Ministries in the provinces had showed themselves in their true colour. Jinnah’s speech at the Aligarh Muslim University Students Union on 5 February 1938 was a revelatory crie de Coeur. “At that time, there was no pride in me and I used to beg from the Congress. I worked so incessantly to bring about rapprochement that a newspaper remarked that Mr. Jinnah is never tired of Hindu-Muslim unity. But I received the shock of my life at the meetings of the Round Table Conference. In the face of danger the Hindu sentiment, the Hindu mind, the Hindu attitude led me to the conclusion that there was no hope of unity. I felt very pessimistic about my country. The position was most unfortunate. The Musalmans were like the No Man’s Land; they were led by either the flunkeys of the British Government or the camp-followers of the Congress. Whenever attempts were made to organise the Muslims, toadies and flunkeys on the one hand and traitors in the Congress camp on the other frustrated the efforts. I began to feel that neither could I help India, nor change the Hindu mentality, nor could I make the Musalmans realise their precarious position. I felt so disappointed and so depressed that I decided to settle down in London. Not that I did not love India; but I felt utterly helpless. I kept in touch with India. At the end of four years I found that the Musalmans were in the greatest danger. I made up my mind to come back to India, as I could not do any good from London. Having no sanction behind me I was in the position of a beggar and received the treatment that a beggar deserves. …

“No settlement with majority community is possible, as no Hindu leader speaking with any authority shows any concern or genuine desire for it. Honourable settlement can only be achieved between equals, and unless the two parties learn to respect and fear each other, there is no solid ground for any settlement. Offers of peace by the weaker party always mean confession of weakness, and an invitation to aggression. Appeals to patriotism, justice and fair-play and for goodwill fall flat. It does not require political wisdom to realise that all safeguards and settlements would be a scrap of paper, unless they are backed up by power. Politics means power and not relying only on cries of justice or fair-play or goodwill…

“The Congressite Musalmans are making a great mistake when they preach unconditional surrender. It is the height of defeatist mentality to throw ourselves on the mercy and goodwill of others and the highest act of perfidy to the Musalman community; and if that policy is adopted, let me tell you, the community will seal its doom and will cease to play its rightful part in the national life of the country and the Government. Only one thing can save the Musalmans and energise them to regain their lost ground. They must first recapture their own souls and stand by their lofty position and principles which form the basis of their great unity and which bind them in one body-politic. Do not be disturbed by the slogans and the taunts such as are used against the Musalmans, – Communalists, toadies, and reactionaries. The worst toady on earth, the most wicked communalist toady amongst Muslims, when he surrenders unconditionally to the Congress and abuses his own community, becomes the nationalist of nationalists tomorrow! These terms and words and abuses are intended to create an inferiority complex amongst the Musalmans and to demoralise them; and are intended to sow discord in their midst and give us a bad name in the world abroad….

“We in India have been brought up in the traditions of the British Parliamentary democracy. The Constitution foisted on us is also modelled more or less on the British pattern. But there is an essential difference between the body-politic of the country and that of Britain. The majority and minority parties in Britain are alterable, their complexion and strength often change. Today it is a Conservative Government, tomorrow Liberal and the day after Labour. But such is not the case with India. Here we have a permanent Hindu majority and the rest are minorities which cannot within any conceivable period of time hope to become majorities. The majority can afford to assume a non-communal label, but it remains exclusively Hindu in its spirit and action. The only hope for minorities is to organise themselves and secure a definite sharein power to safeguard their rights and interests. Without such power no constitution can work successfully in India. …

“What the League has done is to set you free from the reactionary elements of Muslims and to create the opinion that those who play their selfish game are traitors. It has certainly freed you from that undesirable element of Maulvis and Maulanas. I am not speaking of Maulvis as a whole class. There are some of them who are as patriotic and sincere as any other; but there is a section of them which is undesirable. Having freed ourselves from the clutches of the British Government, the Congress, the reactionaries and so-called Maulvis, may I appeal to the youth to emancipate our women. This is essential. I do not mean that we are to ape the evils of the West. What I mean is that they must share our life not only social also political.” (Jamiluddin Ahmad; Speechesand Writings of Mr. Jinnah; Shaikh Mukanwar Ashraf, Lahore; Vol.1,pp. 30 and 43).

Now, perhaps for the first time Jinnah attacked Gandhi unreservedly in his Presidential Address to the League Session at Patna on 26 December 1938. “I have no hesitation in saying that it is Mr. Gandhi who is destroying the ideal with which the Congress was started. He is the one man responsible for turning the Congress into an instrument for the revival of Hinduism. His ideal is to revive Hindu religion and establish Hindu raj in this country, and he is utilising the Congress to further this object.”

The prolonged Jinnah-Gandhi talks in September 1944 were doomed to failure. Their background stretched as far back as 1942 as Ambedkar pointed out. It bears quotation in extenso for its shadow fell even on the events leading to partition. “Mr. Gandhi instead of negotiating with Mr. Jinnah and the Muslim League with a view to a settlement took a different turn. He got the Congress to pass the famous Quit India Resolution on 8 August 1942. This Quit India Resolution was primarily a challenge to the British Government. But it was also an attempt to do away with the intervention of the British Government in the discussion of the Minority question and thereby securing for the Congress a free hand to settle it on its own terms and according to its own lights. It was in effect, if not in intention, an attempt to win independence by bypassing the Muslims and the other minorities. The Quit India Campaign turned out to be a complete failure. It was a mad venture and took the most diabolical form. It was a scorch-earth campaign in which the victims of looting, arson and murder were Indian and the perpetrators were Congressmen. Beaten, he started a fast for twenty-one days in March 1943 while he was in gaol with the object of getting out of it. He failed. Thereafter he fell ill. As he was reported to be sinking the British Government released him for fear that he might die on their hand and bring them ignominy. On coming out of gaol, he found that he and the Congress had not only missed the bus but had also lost the road. To retrieve the position and win for the Congress the respect of the British Government as a premier party in the country which it had lost by reason of the failure of the campaign that followed up the Quit India Resolution, and the violence which accompanied it, he started negotiating with the Viceroy. Thwarted in that attempt, Mr. Gandhi turned to Mr. Jinnah. On 17 July 1944 Mr. Gandhi wrote to Mr. Jinnah expressing his desire to meet him and discuss with him the communal question. Mr. Jinnah agreed to receive Mr. Gandhi in his house in Bombay. They met on 9 September 1944. It was good that at long last wisdom dawned on Mr. Gandhi and he agreed to see the light which was staring him in the face and which he had so far refused to see.

“The basis of their talks was the offer made by Mr. Rajagopalachariar to Mr. Jinnah in April 1944 which, according to the somewhat incredible story told by Mr. Rajagopalachariar, was discussed by him with Mr. Gandhi in March 1943 when he (Mr. Gandhi) was fasting in gaol and to which Mr. Gandhi had given his full approval.

The following is the text of Mr. Rajagopalachariar’s formula popularly spoken of as the C. R. Formula:-

- Subject to the terms set out below as regards the constitution for Free India, the Muslim League endorses the Indian demand for Independence and will co-operate with the Congress in the formation of a provisional interim government for the transitional period.

- After the termination of the war, a commission shall be appointed for demarcating contiguous districts in the north-west and east of India, wherein the Muslim population is in absolute majority. In the areas thus demarcated, a plebiscite of all the inhabitants held on the basis of adult suffrage or other practicable franchise shall ultimately decide the issue of separation from Hindustan. If the majority decide in favour of forming a sovereign State separate from Hindustan, such decision shall be given effect to, without prejudice to the right of districts on the border to choose to join either State.

- It will be open to all parties to advocate their points of view before the plebiscite is held.

- In the event of separation, mutual agreements shall be entered into for safeguarding defence, and commerce and communications and for other essential purposes.

- Any transfer of population shall only be on an absolutely voluntary basis.

- These terms shall be binding only in case of transfer by Britain of full power and responsibility for the governance of India.

“The talks which began on 9 September were carried on over a period of 18 days till 27 September when it was announced that the talks had failed. The failure of the talks produced different reactions in the minds of different people. Some were glad, others were sorry. … Failure was inevitable having regard to certain fundamental faults in the C.R. Formula. There are many faults in the C.R. Formula. The formula did not offer a solution. It invited Mr. Jinnah to enter into a deal. It was a bargain – “If you help us in getting independence, we shall be glad to consider your proposal for Pakistan.” I don’t know from where Mr. Rajagopalachariar got the idea that this was the best means of getting independence. It is possible that he borrowed it from the old Hindu kings of India who built up alliances for protecting their independence against foreign enemies by giving their daughters to neighbouring princes. Mr. Rajagopalachariar forgot that such alliances brought neither a good husband nor a permanent ally. To make communal settlement depend upon help rendered in winning freedom is a very unwise way of proceeding in a matter of this kind. It is a way of one party drawing another party into its net by offering communal privileges as a bait. The C.R. Formula made communal settlement an article for sale.

“The second fault in the C.R. Formula relates to the machinery for giving effect to any agreement that may be arrived at. The agency suggested in the C.R. Formula is the Provisional Government. In suggesting this Mr. Rajagopalachariar obviously overlooked two difficulties. The first thing he overlooked is that once the Provisional Government was established, the promises of the contracting parties, to use legal phraseology, did not remain concurrent promises. The case became one of an executed promise against an executor promise. By consenting to the establishment of a provisional Government, the League would have executed its promise to help the Congress to win independence. But the promise of the Congress to bring about Pakistan would remain executory. Mr. Jinnah who insists, and quite rightly, that the promises should be concurrent could never be expected to agree to place himself in such a position. The second difficulty which Mr. Rajagopalachariar has overlooked is what would happen if the Provisional Government failed to give effect to the Congress part of the agreement. Who is to enforce it? The Provisional Government is to be a sovereign government, not subject to any superior authority. If it was unwilling to give effect to the agreement, the only sanction open to the Muslims would be rebellion. To make the provisional Government the agency for forging a new Constitution, for bringing about Pakistan, nobody will accept. It is a snare and not a solution.” (B. R. Ambedkar, Pakistan Or Partition of India, Thackers, 1946, pp. 407-410).

This was the very technique of cleverness triumphing over fairness which Gandhi adopted in wrecking the Cabinet Mission’s Plan of 16 May 1946. It stipulates a limited federation based on three Groups of provinces (For a detailed analysis vide A.G. Noorani, Jinnah and Tilak; Oxford University press, Karachi;).

A myth grew up that after his election as president of the Congress, in succession to Maulana Azad, Nehru delivered an outburst which killed the plan. What he declared at his press conference on 10 July 1946, achieved that result. Earlier on 7 July he had told the All-India Congress Committee (AICC), “We are not bound by a single thing except that we have decided to go into the Constituent Assembly”. Three days later, he rejected the provisions for grouping.

The Congress would seize the Constituent Assembly, set up under the plan, not as an agreed mechanism as envisaged by the plan itself, but to impose its own diktat while professing to accept it in its ‘entirety’ or ‘as a whole’, i.e. not every part of it.

However, such an assertion of the right to interpret and impliedly to ignore unacceptable parts of the plan, was made by Gandhi at the very outset. He maintained his stand even after the British government declared on 6 December 1946 that the Congress’ interpretation was wrong. Gandhi declared his stand at the very outset and maintained it consistently until the very last. As in 1942, he led from the front.

Volumes 84, 85 and 86, the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, provide a full record of his statements on the Cabinet Mission’s Plan. On 17 May 1946, the very day after it was published, Gandhi said, ‘it was not an award’. The Mission had ‘recommended to the country what in their opinion was worthy of acceptance by the Constituent Assembly’. The Assembly was set up as part of the plan with all its provisions regarding the Groups. Gandhi delinked it from the plan so the assembly could freely enforce the wishes of the Congress majority untrammelled by the plan. ‘The provinces were free to reject the very idea of grouping’. He proceeded to laud the plan, but ‘subject to the above interpretation, which he held was right. This set the policy for the Congress to follow. It was this policy which wrecked the plan. Nehru’s famous outburst came nearly two months later, on 10 July 1946.

In a detailed ‘Analysis’ he wrote in Harijan on 20 May: “Gandhi made no secret of the fact that the sole attraction of the plan was the Constituent Assembly. The Mission’s Plan which created it, could be ignored. In truth, the plan was neither a judicial verdict nor an arbitral award. Like the Cripps offer of 1942, it was a mediator’s recommendation to the contesting parties. If accepted, it became an agreement between the two. The mediator had every right to clarify what was meant by the recommendations, especially since the British were to implement them by legislation. It was open to either side to reject his recommendation or clarification. What neither side could do, however, was to profess to accept it but subject to its own unilateral interpretation. The accord collapses then. If the Congress with its majority in the Constituent Assembly asserted such a right, it could override the provisions regulating its procedure to ensure protection against the majority diktat. Moreover, it challenged the only concession to the Muslim League – the grouping of provinces.”

“It is an appeal and an advice. It has no compulsion in it. Thus the provincial Assemblies may or may not elect the delegates. The delegates, having been elected, may or may not join the Constituent Assembly. The Assembly having met, may lay down a procedure different from the one laid down in the Statement.”

As Congress President Maulana Azad wrote to the Mission on 20 May criticizing the plan and asserting that the Constituent Assembly would ‘be a sovereign body’ which could ‘vary in any way it likes the recommendations and procedures suggested by the Cabinet Delegation…its final decisions will automatically take effect’. Pethick-Lawrence pointed out the obvious in his reply on 22 May. The scheme stands as a whole and can only succeed if it is accepted and worked in a spirit of compromise and cooperation. You are aware of the reasons for the grouping of the Provinces, and this is an essential feature of the scheme which can only be modified by agreement between the parties.

On 24 May, the Congress Working committee passed a resolution on the same lines as its President’s letter. ‘The Assembly would be sovereign… in their view it would be open to the Constituent Assembly itself at any stage to make changes and various with the proviso that in regard to certain major communal matters a majority decision of both the major communities will be necessary’ – impliedly not in regard to changes in the Mission’s Plan itself.

On 24 May, the mission issued an authoritative statement which said; “The interpretation put by the Congress resolution on paragraph 15 of the statement, to the effect that the provinces can in the first instance make the choice whether or not to belong to the section in which they are placed, does not accord with the Delegation’s intentions.”

The British government’s statement on 6 December 1946 concluded on this ominous note: “There has never been any prospect of success for the Constituent Assembly except upon the basis of the agreed procedure. Should the Constitution come to be framed by a Constituent Assembly in which a large section of the Indian population had not been represented, His Majesty’s Government could not, of course, contemplate – as the Congress have stated they would not contemplate – forcing such a constitution upon any unwilling parts of the country.”

If the Constituent Assembly was not worked under the Mission’s Plan, partition would be the only alternative. The Constitution it framed would not be imposed ‘upon any unwilling parts of the country’. But Gandhi was unmoved. His direction to the Congressmen from Assam was clear, for he was untroubled by doubts when he met them on 15 December, ‘I do not need a single minute to come to a decision, for on this I have a mind’. The Federal Court ‘is a packed Court’. It will uphold London’s interpretation. So, ‘as soon as the time comes for the Constituent Assembly to go into sections you will say “Gentlemen, Assam retires” … Else I will say Assam had only manikins and no men. It is an impertinent suggestion that Bengal should dominate Assam in any way’.

Gandhi knew, of course, that his stand rendered partition inevitable; he was unfazed. His note on the Constituent Assembly, dated 17 December 1946, indicates that he was prepared for partition. The Constituent Assembly should frame a Constitution ‘for all the Provinces, States and units that may be represented’ in it. His ‘Instructions to Congress Working Committee’ dated 28/30 December 1946, envisagedpartition and named the seceders from Pakistan –Assam, and the NWFP, ‘the Sikhs in the Punjab and “may be Baluchistan. This will give ‘Quaid-i-Azam Jinnah a universally acceptable and inoffensive formula for his Pakistan”.

The All-India Congress Committee met on 5-6 January 1947 and resolved that ‘it cannot be a party to any such compulsion or imposition against the will of the people concerned’. The Pakistan which Jinnah had rejected in a talk with Cripps on 25 April 1946 now becomes inevitable.”

This demolishes another myth – Gandhi did not want partition. He did. He preferred it to a united India under the Mission’s Plan. On 24 February 1947, Gandhi reacted to the British government’s announcement to quit in these words: ‘This may lead to Pakistan for those provinces or portions which may want it… The Congress provinces … will get what they want’.

He gave a formula on April 4: Jinnah to be Prime Minister of India – backed by a Congress majority in the Constituent Assembly- and liable to a dismissal at any moment. An elaboration of 10 April hinted at partition as an alternative to the League entering the Constituent Assembly. The League was offered an Assembly freed from the Cabinet Mission’s restrictions – with Jinnah as Prime Minister as a sop – or a Pakistan minus the NWFP. When neither worked, he said on 6 May: ‘The Congress should in no circumstances be party to partition. We should tell the British to quit unconditionally’.

He wrote to Mountbatten on 8 May, 1947 asking him to ‘leave the government of the whole of India including the States, to one party’. On 3 June 1947, the Partition Plan was published, which both the parties accepted. The next day Gandhi said; ‘I tried my best to bring the Congress round to accept the proposal of May 16. But now we must accept what is an accomplished fact’ – this was not true, of course, as he well knew. He had led the Congress and it followed him.

His line was clear and consistent: power must be transferred to a Congress government at the centre, which will then deal with the Muslim League. As Ambedkar pointed out, this was the core of the Rajaji formula which Gandhi offered to Jinnah in 1944. This was also his demand in 1947, after the compromise in the Mission’s Plan had been torpedoed by him.

H. M. Seervai’s comment on this iconic figure is fair. ‘It is sad to think that Gandhi’s rejection of the Cabinet Mission’s proposal for an Interim Government, and of the Cabinet Mission Plan, should have had the unfortunate consequence of destroying the unity of a free India for which he had fought so valiantly and so long’.

The frenetic march of events baffled him as they did everyone else. The Congress Working Committee’s demand for partition of Punjab and Bengal on 8 march 1947 implied acceptance of partition of India.

Confronted with the realities that brooked no evasion, Gandhi became desperate. He loathed partition of the country he loved; but he never accepted any compromise with Jinnah which could have averted it. Jinnah did not loathe partition but dreaded it in the only form in which it could be granted. He would have jumped at any sensible compromise, under a smokescreen of assertive rhetoric. He had accepted a Union of India on 25 April 1946, even before the Simla Conference began, and persisted by dropping hints to the British ministers whom he met with in London until December 1946. If only the Congress would drop its crippling conditions, he was prepared to work the Cabinet mission’s Plan. He knew the risks. The Pakistan movement would lose steam. Party discipline would weaken. But the advantages of a compromise to all interests would emerge in bold relief as the processes of conciliation went underway. A constitution can only be drafted in this spirit, with the principal parties sharing power in the interim government while the Constituent Assembly did its job.

This, alas, was the farthest from the minds of Gandhi, Nehru, Patel, and their followers. They preferred the partition of India to a union, which involved power sharing. They had had no practicable compromise formula to offer. The one which Gandhi floated in April 1947 verged on the absurd. It is necessary to peruse his documents to realise how impractical his effort was.

At the end of his interview with Mountbatten on 4 April, Gandhi dictated to the Chief of Staff, lord Ismay an ‘Outline of Draft Agreement’. It read thus:

“Mr. Jinnah to be given the option of forming a Cabinet.

“The selection of the Cabinet is left entirely to Mr. Jinnah. The members may be all Muslims, or all non-Muslims, or they may be representatives of all classes and creeds of the Indian people.

“If Mr. Jinnah accepted this offer, the Congress would guarantee to co-operate freely ad sincerely, so long as all the measures that Mr. Jinnah’s Cabinet bring forward are in the interest of the Indian people as a whole.

“The sole reference of what is or is not in the interest of India as a whole will be Lord Mountbatten, in his personal capacity.

“Mr. Jinnah must stipulate, on behalf of the League or of any other parties represented in the Cabinet formed by him that, so far as he or they concerned, they will do their utmost to preserve peace throughout India. There shall be no National Guards (of the League) or any other form of private army.

“Within the framework hereof Mr. Jinnah will be perfectly free to present for acceptance a scheme of Pakistan even before the transfer of power, provided however, that he is successful in his appeal to reason and not to the force of arms which he abjures for all time for this purpose. Thus, there will be no compulsion in this matter over a province or a part thereof.

“In the Assembly the Congress has a decisive majority. But the Congress shall never use that majority against the League policy simply because of its identification with the League but will give its hearty support to every measure brought forward by the League Government, provided that it is in the interest of the whole of India. Whether it is in such interest or not shall be decided by Lord Mountbatten as man and not in his representative capacity.

If Mr. Jinnah rejects this offer, the same offer to be made mutatis mutandis to Congress.”

On 10 April, 1947 he discussed a related formula with the Congress Working Committee and gave it to Mountbatten the next day, in Hindi, as ‘Gandhi’s draft’. It read:

- So far as Pakistan is concerned and so far as the Congress is concerned nothing will be yielded to force. But everything just will be conceded readily if it appeals to reason. Since nothing is to be forcibly taken, it should be open to any province or part thereof to abstain from joining Pakistan and remain with the remaining provinces. Thus, so far as the Congress is aware today, the Frontier province is with it (Congress) and the Eastern part of the Punjab where the Hindus and the Sikhs combined have a decisive majority will remain out of the Pakistan zone. Similarly in the East, Assam is clearly outside the zone of Pakistan and the Western part of Bengal including Darjeeling, Dinajpur, Calcutta, Burdwan, Minapore, Khulna, 24-Parganass, etc., where the Hindus are in a decisive majority will remain outside the Pakistan zone. And since the Congress is willing to concede to reason everything just, it is open to the Muslim League to appeal to the Hindus, by present just treatment, to reconsider their expressed view and not to divide Bengal.

- It is well to mention in this connection that if the suggested agreement goes through, the Muslim League will participate fully in the Constituent Assembly in a spirit of cooperation. It might also be mentioned that it is the settled policy with the Congress that the system of separate electorates has done the greatest harm to the national cause and therefore the Congress will insist on joint electorates throughout with reservation of seats wherever it is considered necessary.

- The present raid of Assam and the contemplated so-called civil disobedience within should stop altogether.

- Muslim League intrigues said to be going on with the Frontier tribes for creating disturbances in the Frontier Province and onward should also stop.

- Frankly anti-Hindu legislation hurried through the Sind Legislature in utter disregard of Hindu feeling and opposition should be abandoned.

- The attempt that is being nakedly pursued in the Muslim majority provinces to pack civil and police services with Muslims irrespective of merit and to the deliberate exclusion of Hindus must be given up forthwith.

- Speeches inciting to hatred, including murder, arson and loot, should cease.

- Newspapers like the Dawn, Morning News, Star of India, Azad and others, whether in English or in any of the Indian vernaculars, should change their policy of inculcating hatred against the Hindus.

- Private armies under the guise of National Guards, secretly or openly armed, should cease.

- Forcible conversion, rape, abduction, arson and loot culminating in murders of men, women and children by Muslims should stop.

- What the Congress expects the Muslim League to do will readily be done in the fullest measure by the Congress.

- What is stated here applies equally to the inhabitants of princes’ India, Portuguese India, and French India.

- The foregoing is the test of either’s sincerity and that being granted publicly and in writing in the form of an agreement, the Congress would have no objection whatsoever to the Muslim League forming the whole of the Cabinet consisting of Muslims only or partly Muslims and partly non-Muslims.

- Subject to the foregoing the Congress pledges itself to give full cooperation to the Muslim League Cabinet if it is formed and never to use the Congress majority against the League with the sole purpose of defeating the Muslims. On the contrary every measure will be considered on its merits and receive full cooperation from the Congress members whenever a particular measure is provably in the interest of the whole of India.”

In April, 1947 the Viceroy Lord Mountbatten’s talk with the leaders was in full swing and reached a breakthrough by May. Not surprisingly, because only one option was open –partition of India and the provinces of Punjab and Bengal.

Gandhi’s exertions need not have frightened Mountbatten since Gandhi had no sensible alternative to offer. But the Viceroy was worried lest Gandhi threw a spanner in the works and wrecked the understandings that had been reached. Mountbatten gave full vent to his feelings against Gandhi in private communications.

In his personal report dated 5 June 1947, he wrote: “Since Gandhi returned to Delhi on 24 May, he has been carrying out an intense propaganda against the new plan (for partition), and although I have always been led to understand he was the man who got Congress to turn down the Cabinet Mission plan a year ago he was now trying to force the Cabinet Mission plan on the country. He may be a saint but he seems also to be a disciple of Trotsky.”

On 2 July 1947, the Viceroy wrote to Prime Minister Attlee, ‘My private opinion is that Gandhi is adopting his usual Trotsky attitude and might quite well like to see the present plan wrecked, so he is busy stiffening Congress attitude’.

On 4 July, Mountbatten repeated this, by now favourite, expression in his personal report: “The attitude of Gandhi continues to be quite unpredictable and as an example of what I have to contend with I attach as appendices ‘A’ and ‘B’ a copy of a letter I received from him dated 27 June, together with the reply I sent him on the next day. Needless to say everything he wrote in his letter was a complete misrepresentation, either deliberate or otherwise, of what I had said to him. He is an inveterate and dangerous Trotskyist.” Publication later of the relevant Volumes of the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi revealed his hatred for Jinnah.

It was hard to understand him. In 1947 Gandhi opposed the admission into the first Cabinet of free India not only Ambedkar but also Azad. The Governor of Bengal, Richard C. Casey, reported to Viceroy Wavell on 2 and 3 December 1945 his talks with Gandhi, when the visitor said that ‘he believed Jinnah to be a very ambitious man and that he had visions of linking up the Moslems of India with the Moslems in the Middle East and elsewhere and that he did not believe that he could be ridden off his dreams. That prospect was farthest from Jinnah’s mind. The charge was a bit too much from an ardent Khilafatist of former years in respect of a known sceptic.”

Nor was Nehru spared. Gandhi wrote to Nehru on 17 January 1928: “If any freedom is required from me I give you all the freedom you may need from the humble but unquestioning allegiance that you have given to me for all these years and which I value all the more for the knowledge I have now gained of your state. I see quite clearly that you must carry on open warfare against me and my views. For, if I am wrong I am evidently doing irreparable harm to the country and it is your duty after having known it to rise in revolt against me. Or, if you have any doubt as to the correctness of your conclusions, I shall gladly discuss them personally. The differences between you and me appear so vast and radical that there seems to be no meeting ground between us.” (Uma Iyengar and Lalitha Zachariah [Ed.]; Together They Fought; Gandhi-Nehru Correspondence, 1921-1948; Oxford University Press; p. 56).

None who differed and stood up to him was spared. Subhas Chandra Bose, Ambedkar, and Azad. Nehru realised that he had nowhere to go if he broke with Gandhi. But Jinnah stood up to Gandhi effortlessly and without rancour. The Nagpur rift did not affect him. Gandhi’s refusal to negotiate in 1937-38 did. Unlike them Jinnah was not a subordinate. He was in Indian politics before Gandhi and had mentors like Gokhale who was superior to Gandhi. Jinnah was superior to all of them, Sapru and Jayakar were not his peers.

The last word belongs to a writer of outstanding qualities, Ved Mehta “Jinnah left the Congress in 1920, just when – and, in fact, because – Gandhi was rising to power in it. He disdained Gandhi’s religious attitude towards politics, his civil disobedience campaigns, his fasts and marches. Jinnah became the spokesman of the Muslim, who came to regard Gandhiji’s pleas for Hindu-Muslim toleration as a means of perpetrating Hindu domination. Gandhi’s idea of Hindu-Muslim toleration seemed visionary and unpractical to Jinnah, especially since Gandhi sometimes referred to independent India as the Hindu Ram Rajya. Jinnah became the founder of Pakistan. Gandhi had many previous adversaries in his life, but none of them had ever aroused his passion or made him despair as Jinnah did. Up to then, in everything Gandhi had said, done or written there had been a current of optimism, which flowered out of his un-shakable faith that providence guided human destiny. That optimism had begun to diminish. He stopped talking about living to be a hundred and twenty five, and started calling himself such things as a spent bullet.” A fair summing up.