By Jamil Nasir[*]

Abstract

This paper analyses the binding constraints to sustainable economic growth in Pakistan within the growth diagnostics framework developed by Hausmann et al. Factors like limited access to finance, low returns to economic activity, and low appropriability of returns are discussed at length in the light of data and literature. Low financial inclusion, weak financial intermediation, and low human capital formation are serious concerns but do not constitute binding constraints to sustainable economic growth. Similarly, shortage of electricity, poor law and order, and security concerns are constraints to economic growth but all these problems are connected to poor institutional quality and bad governance. The critical constraints in case of Pakistan are what the growth diagnostics framework calls ‘micro-risks’ like weak property rights, corruption, etc. The paper concludes that weak institutions and poor governance are in fact the binding constraints to economic growth. Pakistan needs to revamp its slow-moving judicial system to enforce property rights and contracts. Pakistan should introduce structural reforms to improve functioning of institutions and governance. Private and public sectors need to join hands to foster productivity. Such reforms are not only doable but desirable to ignite growth, when the country is faced with scarcity of capital and resources. Author)

Introduction

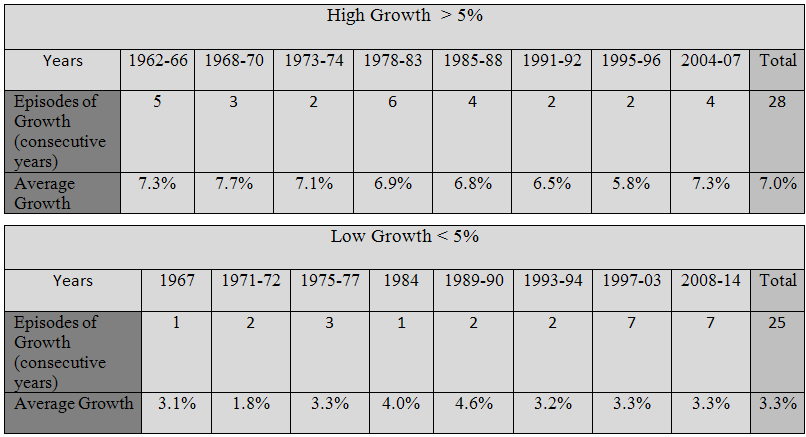

Raising the rate of economic growth in a sustainable manner is the most daunting challenge for Pakistan. There is no reliable and unambiguous answer to the question of how to promote it. Consensus exists only on two points. First, Pakistan has high untapped potential of economic growth and if binding constraints are removed, it can be put on the trajectory of higher economic growth. Second, Pakistan should grow at the rate of above 7% at least for two decades to provide employment to its burgeoning youth population otherwise a big social and political disaster is in the waiting. The fact is that the growth potential of the country is not being adequately exploited. The growth pattern over the last fifty years shows that Pakistan has experienced few short-lived spurts of economic growth. Out of the last 53 years, for 28 years Pakistan’s growth rate was above 5% while for 25 years, the growth rate was on average 3.3%. Since 2007, Pakistan has entered into a low spiral of economic growth. This low growth cycle is the longest in the economic history of Pakistan (Table1).

Table 1: Growth Booms and Busts

Source: J.R Lopez-Calix et al, World Bank Policy Paper series, Dec, 2012; Analysis extended up to

2014 by the author

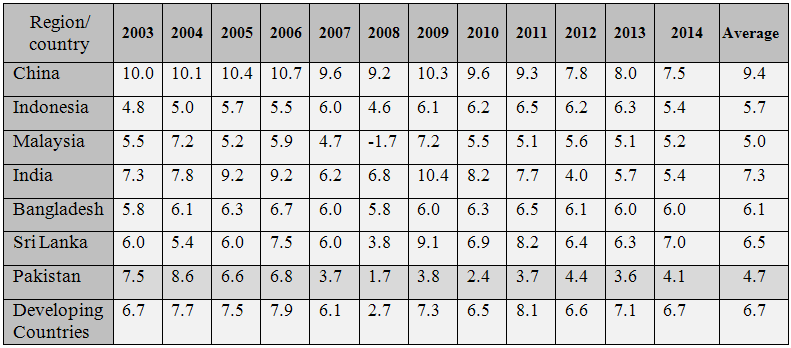

Before delving into the analysis regarding binding constraints to economic growth, let us look at some of the stylized facts about economic growth in Pakistan. First, the growth cycle of Pakistan can best be described as busts and booms[1]. Till 1990 Pakistan enjoyed a respectable growth and after that a declining trend is very much visible except for the high-growth episode of 2004-07 when Pakistan enjoyed an average of 7.3 % growth rate. Second, Pakistan’s growth rate is diverging from its comparators with each passing year (Table2).

Table 2: Comparative Real GDP Growth Rates (%)

Source: World Economic Outlook (IMF), various reports

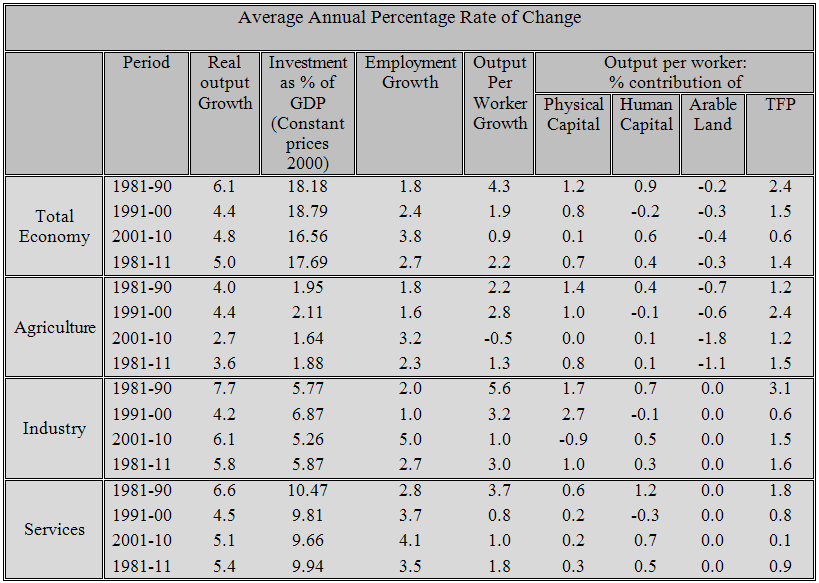

Table 3: Pakistan Sources of Annual Growth in Labour Productively, 1981-2011 Third, Per capita income of Pakistan is also fast diverging with its comparators like India and China due to low growth rates. Fourth, composition of growth determinants indicates that productivity is showing a steady fall during the 2000s and that economic growth in the past few decades was mainly driven by physical and human capital and was not due to productivity growth, as measured by total factor productivity (TFP)[2]. Fifth, unsustainable economic growth is essentially related to falling productivity (Table-3)

Source: J.R Lopez-Calix et al, World Bank, 2012

What are the missing conditions in Pakistan which restrict Pakistan from achieving high and sustainable growth? Various studies and papers have tried to find out an answer to this question and have come up with a plethora of interlinked factors for Pakistan’s growth slide. Low human capital formation, political instability, bad governance, insufficient infrastructure, and high macroeconomic risks are some of the constraints identified by such reports. Such findings are very similar to the prescriptions of ‘Washington Consensus’. In the 1990s, ‘Washington Consensus’ advocated a similar set of reforms which were considered a panacea for unlocking the economic potential of a developing country. The Washington Consensus policies came as a part of conditionality with economic assistance from the IMF and the World Bank but the results of such policies varied from country to country. The key findings of the 1990s development experience were: one, economic growth was critical for poverty reduction. Two, uniform policy packages do not translate uniformly into growth across countries. Third, country-specific strategies concentrating on the binding constraints to growth are more likely to produce good results[3]. It means that poor and developing countries may be lagging in sustainable economic growth due to variegated factors and perhaps Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina’s opening lines that happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way, is very much true in their case. So, the need was felt to find out the top most constraint to economic growth in a country. It is in this context that the growth diagnostics framework was developed by Professor Ricardo Hausmann et al[4].

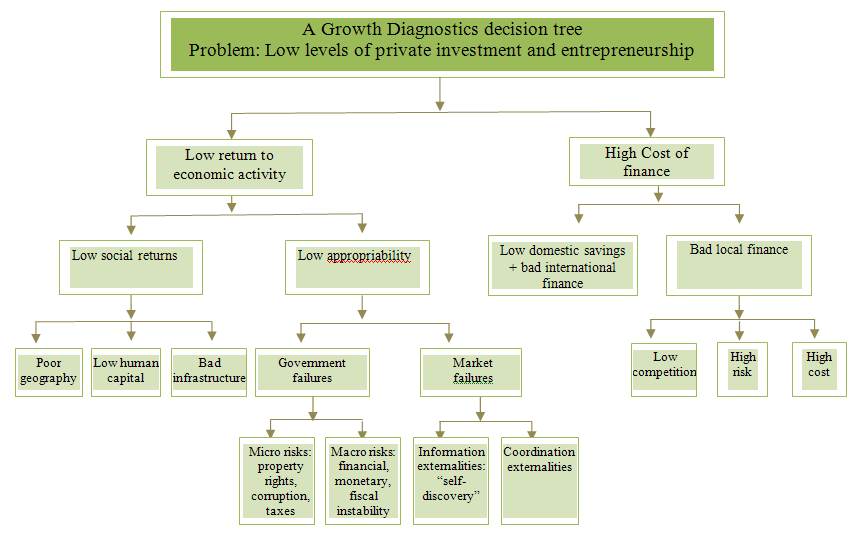

Growth Diagnostics Framework

The Growth Diagnostics Framework begins with the recognition that the developing countries which have grown economically did follow various rules of good economic behaviour like maintaining macroeconomic stability, enforcement of property rights, improving human resources, improving infrastructure, etc. Moreover, neither one-size-fits-all strategy is desirable nor a big laundry list of policy reforms is required. Instead, each country needs to identify the most binding constraint (s) and formulate growth policies to alleviate such constraint(s). Thus the growth diagnostics framework shows disenchantment from the ‘Washington Consensus’ policy prescriptions which were uniform for all the developing countries. In some cases, these prescriptions worked while in most cases they failed badly. So the growth diagnostics framework is premised on the assumption that constraints to economic growth may differ from country to country. Each country should search for such constraint (s) to unlock its growth potential.

But a question can be raised here: Is everything not binding in a developing country? Responding to this question, Professor Ricardo Hausmann writes[5] “It is tempting to think that in a poor country, everything is binding because everything is in a poor shape. But it is unwarranted to think that all dimensions are binding at the same time. Yes, infrastructure is lousy, banks are not Swiss and schools leave lot to be desired. However, education may be lousy but other things may also be so much worse that high-skilled individuals are either leaving the country or driving taxis. The banking system may be small, but banking may be full of liquidity and desperate to find sound customers to lend money to at very sensible rates—- The growth diagnostics framework thus asks the question, which one (constraint) if relaxed ,will deliver the biggest bang for the effort?”

The growth diagnostics framework recognizes that economic growth is central to development and poverty reduction. Its underlying assumption is that not all constraints bind equally and a sensible and practical strategy is to find the most binding constraint (s) at work.[6] The framework is rooted in the principles of neoclassical economics and allows the policy makers to creatively develop policy designs which address the most binding constraint while taking into account the relevant economic, social, and economic factors. The growth diagnostics framework is, however, not free from criticism.

Its critics say that it lays much emphasis on private investment and thus advocates ‘capital fundamentalism’. The methodology adopted is static in nature as it focuses on constraints which are binding today but may not necessarily be binding in the future.[7] The approach adopted by the framework is to detect the constraint to igniting growth whereas in most of the developing countries, the problem is to sustain economic growth in the medium and long-term. The growth diagnostics approach, however, represents the other extreme of the Washington consensus approach to reforms. If the Washington consensus suffers from the laundry list of reforms, ( meaning that everything should be reformed), it is also difficult to believe that only one constraint is the most binding constraint to economic growth in a country, given the complexity of the growth process.

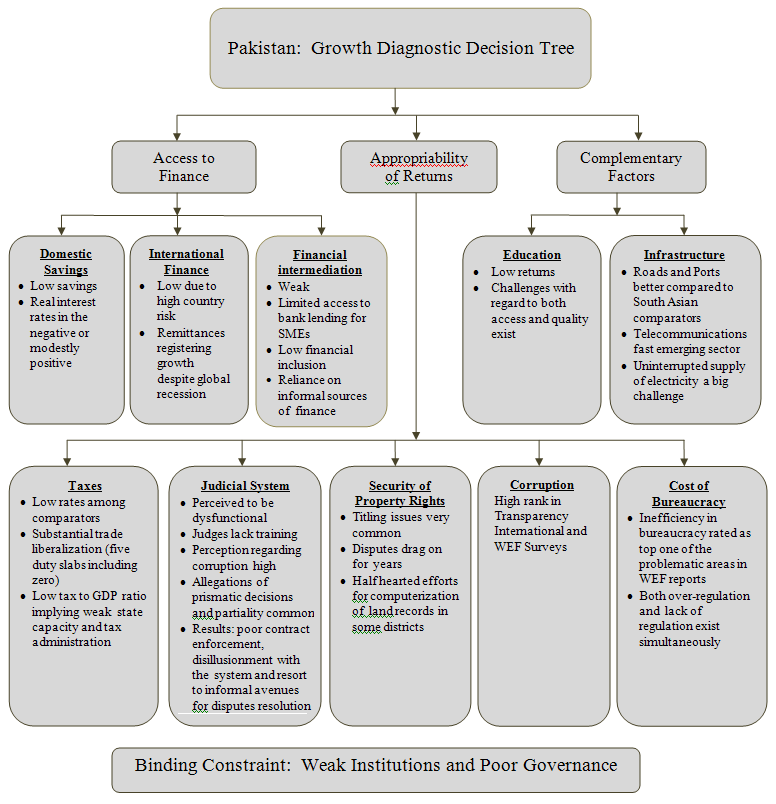

Going Down the Decision Tree

The search for binding constraint within the framework of growth diagnostics starts with three broad categories i.e. access to finance, appropriability of returns, and availability of complementary factors of production. It means that we have to find out whether growth is constrained because the investors and the entrepreneurs cannot get the capital to start businesses and implement their ideas, or they cannot get sufficient returns for their efforts and do not want to invest despite availability of finances and capital, or complementary factors like public infrastructure, institutional infrastructure (enforcement of contracts, protection of property rights), or skilled labour is lacking. If it is access to finance, then we have to see whether this constraint stems from low domestic savings, or lack of access to foreign savings, or weakness in financial intermediation.

Figure 1

(i) Low domestic savings

Traditionally, Pakistan’s savings have been low compared to its comparators like India and China. Pakistan’s national savings increased in the early 2000s due to an improved macroeconomic environment and substantial increase in foreign remittances. Since 2005-06, Pakistan’s savings have persistently declined. In 2005-06, domestic savings were 13.4% of the GDP which have almost been halved by 2013-14 when the domestic savings were estimated to be 7.54 % of the GDP as per the Economic Survey of Pakistan, 2013-14. National savings of Pakistan are estimated at 10-12 % of GDP during the 2000s, whereas, in case of India and China savings rates are estimated respectively above 30 % and 40%. Low savings are thus one the major culprits for low investment and hence low growth in Pakistan. Private investment has also gone down gradually. In 2005-06, private investment in terms of GDP was 13.5% which stood at 8.9% in 2013-14[8]. Such an investment rate is estimated to be three to four times lower than those of India and China.

What are the main reasons behind low savings and investment in Pakistan? Low tax revenue is perhaps the main culprit. Pakistan has the lowest tax-to-GDP ratio in the world. Most of the revenue collected is devoured by current expenditures. Development expenditure is far lower compared to current expenditure. Public investment during 2005-13 has hovered around 3% of GDP. Subsidies to state owned enterprises (SOEs), security, contingency expenditures, and salaries to the public sector utilize public sector investment. In order to fill the savings-investment gap, Pakistan has to rely on foreign inflows or the reserves get depleted. Foreign inflows have always got an element of volatility and pressure on reserves creates unsustainable current account deficits and macroeconomic instability. Against this backdrop, Pakistan needs to increase its own savings for sustainable economic growth and it will not be possible unless it takes serious and politically tough decisions for domestic resource mobilization, especially raising revenue through indirect taxes like income tax and wealth tax.

What are the reasons behind low investment in Pakistan? Is it due to high cost of finance or due to low private returns? Certainly, private investment in Pakistan is low. The culprits for low savings are very much obvious. Terrorism, poor law and order situation, political and economic uncertainty, crowding out of credit to the private sector (commercial banks feel more secure in retaining public securities as the government is a frequent borrower), and lack of developed capital markets which can channel savings to good investments are some conspicuous factors responsible for the low savings-low investment phenomenon. But low domestic savings do not appear to be the binding constraint in case of Pakistan. According to literature on the issue, the lowness of savings as binding constraint to economic growth can be determined from the indicators like levels of foreign debt, current account deficit, and real interest rates. If these variables are high, then low savings are a potential candidate to become the binding constraint to growth.

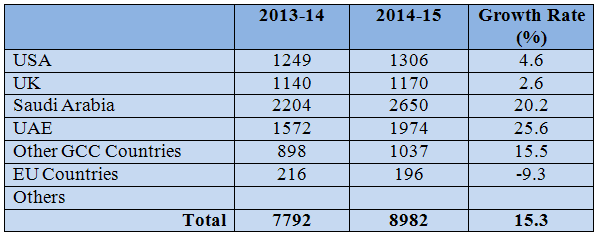

The foreign currency debt in terms of GDP has decreased from 46.9% in 1996-97to 22.8% of GDP in 2011 as per the Debt Policy Statement, though overall public debt has registered a huge increase which was estimated at 61.5 % of GDP in 2011-12.The current account deficit during the last ten years was not that bad except for the years 2006-7 to 2008-09 when imports registered an unprecedented increase. During 2001-02, 2002-03, 2003-04 and 2010-11, current account was rather in surplus. The real interest rates in Pakistan have mostly remained in the negative. For example, in 2008 and 2009 the real interest rate was (-) 1.0 % and (-) 2.6% respectively. Since FY 2010, real interest rates have turned slightly positive. The current account deficit is average in terms of international benchmarks. Foreign remittances have gradually increased and have witnessed a steady increase even after the global financial crisis of 2008. Despite all such odds, remittances have shown steady growth. Even during the first six months of the current fiscal year, remittances have shown a growth rate of 15.3%. A big increase in remittances has been observed from Middle East countries (Table 4). Remittances from USA and UK have shown modest growth but there is a slight decrease from EU due to recession in these countries[9].

Table 4: Home Remittances by Source ($ million)

Source: Economic Data, State Bank of Pakistan (July to December 2014)

(ii) Weak intermediation

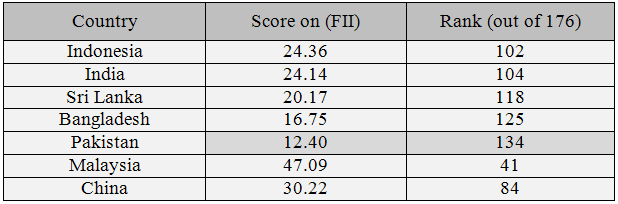

But it does not mean that availability of finance for the investors and entrepreneurs is an easy job. Weak financial intermediation, high collateral requirements, and financial illiteracy are the biggest stumbling blocks to the availability of finances in Pakistan, especially for small and medium enterprises. Financial inclusion is one of the big challenges. Pakistan lags behind all its comparators in terms of financial inclusion[10] (Table-5).

Table 5: Financial Inclusion Index (FII)

Source: Financial inclusion, Poverty, and Income inequality in developing Asia (January, 2015 ADB Economics Working Paper Series)

Financial inclusion is highly important for poverty reduction and promoting entrepreneurship. Jim Kim, the World Bank President in a blog on financial inclusion for poverty reduction writes, “People who are unbanked struggle to save, plan for the future, start a business, or recover from unexpected losses. Small businesses without access to affordable financial services or credit cannot acquire capital to invest, grow, and create jobs. Financial access provides the building blocks people and businesses need to manage their economic well-being, and promote savings, investment, job-creation, and growth. Financial access also empowers women by making it easier for them to build wealth and create small businesses.” [11]

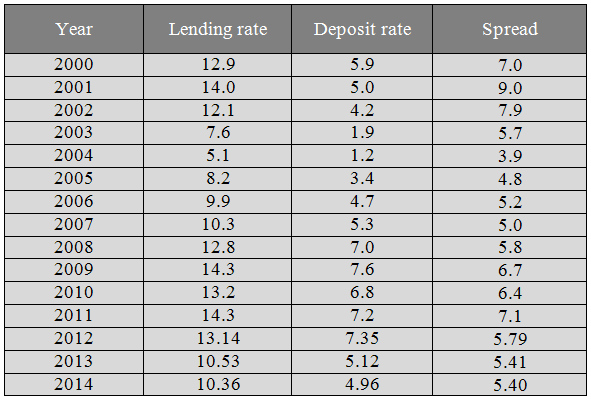

Pakistan embarked on structural reforms during 1990s in the banking sector with a view to make the banking sector more efficient. Such reforms certainly reduced the footprint of the public sector in banking but in terms of access, banking sector leaves much to be desired. Most of the population, especially in the rural areas, still does not have access to banking services. High interest rates though do not appear to be a binding constraint but high intermediation costs, evident from high interest rate spreads, are a real concern. The lending rates are comparatively high due to preference of the commercial banks to hold public securities. Deposit rates are low as deposits are held in the banks for transactional purposes and banks as such do not attract savings of the people. Banking spreads are persistently high. (Table-6)

Table 6: Lending and Deposit Rates

Source: Economic data, State Bank of Pakistan

An average Pakistani household is still outside the formal financial system and does not use the banking system for deposit of their savings. Over half of the population saves but only 8% entrust their money to formal financial institutions. One-third of the population borrows but only 3% use formal financial institutions. Microfinance has grown in the last one decade in Pakistan but out of about 80 million adults, microfinance access extends to only 1.7 million. About half of the population uses informal sources of credit where interest rate charged in most cases is exorbitantly high.Pakistan’s monetary policy is operating in an environment where fiscal deficits and government debts are increasing and government is continuously borrowing from the central bank[12]. Lending-deposit interest spread is a good measure of financial efficiency. Large interest rate spreads in Pakistan among other factors are driven by the opportunities for the banks to earn income from non-core business activities[13]. Domestic financial constraints in Pakistan are also driven by lack of financial depth.

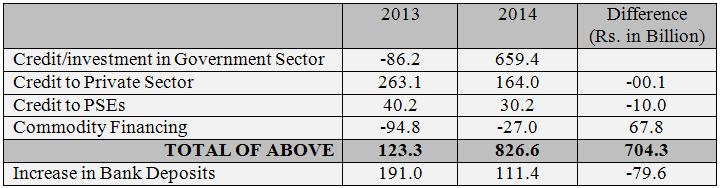

SMEs are considered the growth engines of the economy as they provide jobs, foster entrepreneurship, and provide depth to the industrial base of the economy. But SMEs get a disproportionately small share of credit relative to their contribution to the overall economy of the country. According to World Bank estimates, there are over 3.2 million SMEs in Pakistan which constitute about 90 % of the private enterprises in the industrial sector, employ nearly 78% of the non-agriculture labour force, and contribute over 30% to the GDP but receive about 16% of the total lending to the private sector. Massive borrowing by the government from scheduled banks has also crowded out the private sector. For example, during six months of the current fiscal year, credit to the private sector has decreased by 37.6 % over the corresponding period of the last year[14] (TABLE).

Table 7: Flow of Bank Credit

Source: Economic data, State Bank of Pakistan (1st July to 26th December 2014)

According to a study[15], economic and cultural factors like poverty, financial illiteracy, and religious beliefs also hinder access to finance. Resultantly, most of the individuals and small firms use informal sources of borrowing rather than having to resort to financial institutions. Undoubtedly, weak financial intermediation, low financial inclusion, and reduction in credit to the private sector are big problems but these problems have existed for a long time. Even during the periods of growth accelerations, such problems existed except during President Musharraf’s interregnum, when due to a loose monetary policy, money supply to the private sector was high. Foreign remittances have always been a big source of finance but the exogenous sources of foreign funds have not translated into productive investment. Generally, such flows ended up in real estate with a result of surge in real estate prices. “Had the economy been constrained by low savings the surge in remittances would have found way into productive investment rather than in real estate”[16].

(iii) Bad international finance

Due to terrorism and violence, Pakistan is perceived to be a high risk country. WEF’s Global Competitiveness Report 2014-15 has ranked Pakistan 139 out of total 144 countries against the indicator of ‘business costs of terrorism. When the present government came into power, it was expected that private investment will pick up but major stumbling blocks to foreign investment like the bad security situation, poor law and order conditions, especially in Karachi, and the shortage of electricity still exist. Private investment has witnessed a dip. It has declined by 1.6% in real terms in 2013-14. A large fall of 27% has been observed in the large- scale manufacturing sector. Despite the signing of many agreements and MOUs, investment in the power sector has declined by over 9%.[17] “The reduction in external inflows has aggravated internal and external financing issues. Pakistan has increasingly relied on monetary and central bank financing of the current account and fiscal deficits. The diversion of commercial financing to government bonds issued to finance the fiscal deficit has reduced credit for the private sector, which has particularly affected SMEs and women entrepreneurs.”[18]

Concern about finance, however, also reflects other constraints on borrowers which are not necessarily linked to availability of credit. For example, access to finance, especially to small firms, is constrained due to financial illiteracy and limited capacity to produce necessary documentation like a business plan, licence, title for collateral. Second, flow of remittances has remained steady in case of Pakistan. Third, evidence suggests that financial intermediation in Pakistan is weak but Pakistan has taken a number of reforms in the banking sector in 1990 by reducing the state’s foot print on the financial sector, so there is little evidence to suggest that it has recently become a critical constraint on growth. Moreover, if Pakistan were to suffer from dearth of capital constraining entrepreneurship, returns on factors like land should have been low. Anecdotal evidence suggests that real estate prices have rapidly appreciated in recent years. On balance, access to finance does not seem to be a major binding constraint on growth in the growth diagnostics framework where we have to search for the top constraint.

Low returns to economic activity

According to the Growth Diagnostics Framework, low levels of private investment and entrepreneurship can also be due to low returns on economic activity. Firms and entrepreneurs might have access to finance but they might not pursue any new ventures due to expected returns. According to the framework, low returns to economic activity can either be due to low social returns or a low appropriability of otherwise high returns. Low social returns on factors of production can be due to three broad factors i.e. poor geography, bad infrastructure, and low human capital.

(i) Is it poor geography?

Some empirical evidence suggests that geography has a deep nexus with growth. Geography is said to have long-term effects on economic development. For example, Professor Sachs claims that low economic growth in tropical countries can partly be explained by their location. These countries face at least two ecological handicaps in the form of low agricultural productivity and a high burden of disease.[19] Similarly Jared Diamond has argued that proximate determinants of the economic and political success of Europe were outcomes of deeper geographic advantages from prehistoric times.[20] Whether a country is landlocked or not has also got relevance with regard to economic growth of a country via channel of international trade. Pakistan is endowed with excellent geography. Its location is strategic, having natural geographical connections with China, India, and Russia through Central Asia. “It is at the fulcrum of huge market with increasing population/ workforce, diverse resources, and growing but untapped potential for trade. With its advantageous geography, Pakistan is destined to become a trade hub.”[21] Thus poor geography is not a binding constraint for economic growth.

(ii) Is it bad infrastructure?

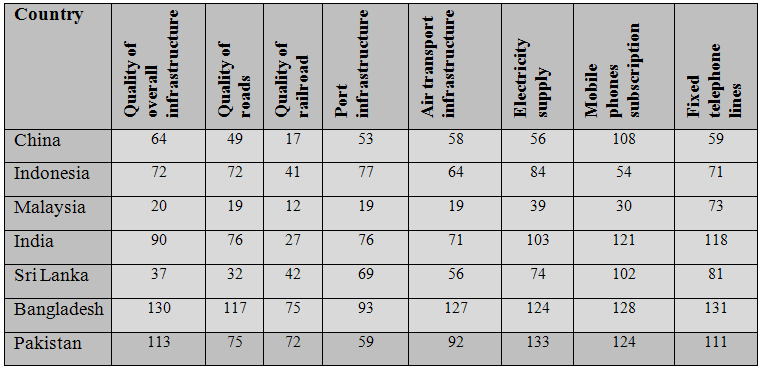

According to the Global competitiveness Report 2014-15, Pakistan has been ranked 133 out of a total of 144. However, an analysis of various categories of infrastructure shows that in terms of quality of roads, Pakistan has been ranked at 75, better than Bangladesh (117), India (76), and very close to Indonesia ( 72). With regard to Port structure, Pakistan’s ranking is 59 and it fares better than Bangladesh (93), Sri lanka (69), India (76), and Indonesia (77). Pakistan, however, fares low among the comparators in terms of supply of electricity (133). (TABLE)

Table 8: Infrastructure

Source: World Economic Forum (WEF) Global Competitiveness Report 2014-15

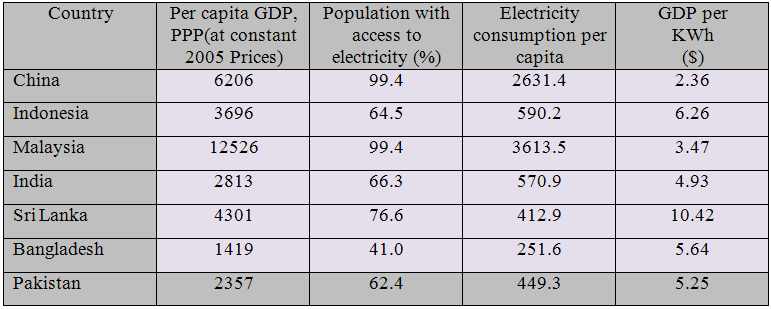

According to the World Bank[22] “Pakistan’s public infrastructure has improved over the last 50 years, but slowly, resulting in many gaps that place the country at a disadvantage to competitor countries such as Egypt, Malaysia, and Sri Lanka, where investment has been greater and progress faster—- It has among the lowest electricity generating capacity and the highest power losses of the comparator countries. Even worse, institutional shortcomings hold electricity generation below capacity, resulting in systematic power outages and load-shedding. Access to potable water and improved sanitation is well below that in comparator countries.” But the question here is: whether shortage of electricity is solely an infrastructural issue? Certainly not. The energy sector is in doldrums due to an “unreliable mix of power sources, generation and distribution losses due to aging infrastructure, fiscal deficits, and governance issues.” The National Power Policy 2013 of the Government of Pakistan also recognizes that Pakistan’s power sector is terribly inefficient and records 15-23% losses due to poor infrastructure, mismanagement, and theft of electricity. Theft alone is estimated to be costing the national exchequer over Rs 140 billion annually.[23] Pakistan has the lowest per capita consumption (except Bangladesh) among its comparators. Interestingly, Per capita GDP and per capita consumption of electricity seems to have a direct correlation, implying that access to electricity is one of the main determinants of growth and development of a country (TABLE).

Table 9: Indicators of Electricity Consumption in Selected Countries

Source: World Bank, World Development Indictors (WDI). These are based on data for year 2009

(iii) Is it low human capital?

Pakistan has some of the worst human development indicators in the world. For example, out of 1000 children born in the poorest quintile, 94 die within twelve months and 120 die within five years. Equality of opportunity remains an elusive goal. In terms of access to basic services, many children are still suffering from discrimination because of their socioeconomic background. Girls have fewer chances than boys to study because of cultural and social reasons. Girls in the age bracket of 12-18 years have both lower secondary school attendance rates and lower completion rates than boys of the same age group. The difference in attendance rates between boys and girls is as high as 14 percentage points.[24]

According to the World Bank,[25] “several cultural factors shape the speed of human capital gains in Pakistan. Only 21% of Pakistani women, compared with 82% of women, participate in the labour force, well below the South Asian average of 4 6% and averages in other regions. At more than 50%, idleness – not in school or training, not employed, and not looking for work – among Pakistani women is the highest in the world. Women with a higher education are less likely to enter the labour force than women with no education, except for women in urban areas with a pre-university and above education. Marriage is associated positively with labour force participation for men and negatively for women.”

At present, Pakistan’s education system ranks among the least effective. One in ten of the world’s primary-age children who are out of school live in Pakistan. This makes the country second in the global ranking of out-of-school children after Nigeria. According to UNESCO estimates, 30 per cent of Pakistanis live in extreme educational poverty. Education and skill levels of the workforce are low and one may hypothesize that low supply of human capital is a constraint to growth. This, however, is not the case. The problem is on the demand side. If the problem is a low supply of educated workforce, then the logical corollary is that returns on education should be higher which means that the market is willing to pay more to the educated few but this is not the case. The returns to education, for both male and female, have declined in the last couple of years. Low quality, low skill levels, less emphasis on honing of cognitive and analytical skills in educational institutions, low budget allocations for education, more focus on rhetoric than content, least priority to technical and vocational education and training, and cultural barriers to female education all are responsible for low human capital formation in Pakistan.

But human capital is certainly not a binding constraint to economic growth in Pakistan as suggested by the following. First, returns to education are not high in the country. Rather returns on education have decreased in the last couple of years. If education were a binding constraint to growth, then expected returns for educated people would have been high. Second, educated people would have been coming to Pakistan from other countries for jobs in case returns to education were high in Pakistan. Instead, Pakistani youth are migrating to other countries to seek jobs and there is an increasing brain drain from Pakistan. Third, anecdotal evidence suggests that Pakistani firms and businesses are not investing heavily into the training of staff nor are they in search of qualified workers from the international labour market for hiring. So we can conclude that low human capital development is not a binding constraint to growth in Pakistan.

Appropriability of Returns

Let us now explore the factors weakening the appropriability of returns and thus discouraging investment, business activity and economic growth. According to Growth Diagnostics Framework, low appropriability of returns may be due to market failures (information externalities and coordination externalities) or due to government failures (high taxes, poor enforcement of property rights, corruption).

(i) Market failures

Productivity is low across all sectors of economy in case of Pakistan. Product diversification especially in exports is low. Pakistani exports are concentrated in a few sectors like textile, leather, sports goods, and footwear. This phenomenon raises concern regarding export dynamism.[26] Pakistan’s share in high-tech contents (which hovers around 2%) has not changed since the 1980s whereas the share of low-tech exports has increased considerably. In terms of destination, Pakistan’s exports have witnessed improvement in diversification in the last decade with a small rise in exports to the Russian Federation, India, and China. Though it has not diversified its export products there has been, nonetheless, an appreciable increase in the number of exporting firms. According to a World Bank report,[27] ‘low level of innovation exchange in Pakistan is long-standing structural constraint to its growth. Innovation promotes productivity, job creation and knowledge sharing.

Innovation exchange is directly related with Pakistan’s performance in export sophistication and productive diversification. Pakistan is ranked lowest on three global innovation indexes— global innovation, global competitiveness, and innovation capacity.” Low learning and poor coordination are certainly problems. Private investment in developing countries like Pakistan certainly depends on complimentary public investment which is no doubt low in case of Pakistan. But low level of diversification has a nexus with government failures and cannot be attributed to the private sector only. Successive governments have failed to provide an enabling environment to the private sector. For example, clear and consistent rules of the game are prerequisites for private sector growth but such rules are found lacking in Pakistan.

(ii) Government Failures

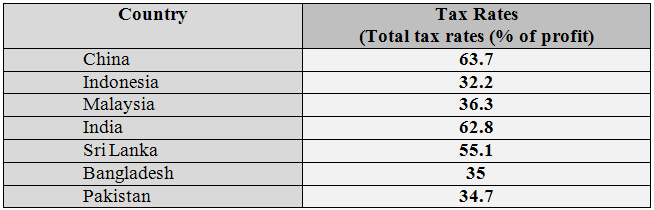

When we talk of government failure the first suspect that comes to mind is high taxation, as entrepreneurs would hesitate to invest if a major chunk of their profit is taken away by the state through taxation. A huge informal sector in Pakistan can also lead to speculation that the taxation structure of Pakistan is complex. But, interestingly, Pakistan has the lowest tax rate among its comparators (except Indonesia) as is evident from the following table.

Table 10: Tax rates

Source: World Economic Forum (WEF) Global Competitiveness Report 2014-15

However, it can be argued that it is not only the tax rate which matters. Cumbersome tax procedures and complexity of tax codes also discourage growth of businesses. This argument is valid to some extent in the case of Pakistan as well. But the taxation history of Pakistan shows that Pakistan has instituted numerous reforms, though mostly as part of conditionality of the World Bank and IMF, to simplify and modernize its tax and trade regime. These reforms have shown some success. For example, Customs procedures have been simplified and tariffs rationalized. Pakistan’s recent reforms have been substantial. Its trade regime is now one of the most open, at least in South Asia. It has the lowest applied average tariff rates of the three large South Asian economies i.e. India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Pakistan eliminated quantitative restrictions, regulatory duties and other Para- tariffs and several other measures that restricted trade in the past. Now ordinary custom duties are the only principal instrument of the trade policy. Maximum tariff has been reduced to 25 percent from 80 percent in 1995 with a simple average applied rate of 15 percent compared to 51 percent in 1995. The number of regulatory duties has declined significantly. Virtually all tariffs (99.3%) are ad-Valorem and revolve around only five slabs including the slab of zero. Local content requirements have been eliminated in all sectors and policies have been brought in compliance with TRIMS agreement of WTO. Briefly put, Pakistan’s tax rates and duty structure is better than the regional average.

But Pakistan has persistently failed to increase tax-to-GDP ratio which has declined in the last couple of years. Low tax-to-GDP ratio points towards weak state capacity and poor governance. The ability to raise taxes is considered the best proxy for state capacity. Low capacity simply means that the state is unable to make people pay their due taxes due to multiple factors like weak rule of law, corruption, and poor tax administration, all symptoms of poor governance. The conclusion, therefore, is that tax rates and duty structure are not a binding constraint for economic growth in Pakistan though Pakistan has failed to make the elite pay their taxes.

(a) Enforcement of property rights

Security of property rights is considered vital for economic growth. Economists have emphasized four main channels[28] through which property rights affect economic activity. First, expropriation risk—insecure property rights imply that individuals may fail to realize the fruits of their investment and labour. Second, insecure property rights lead to costs which the individuals have to bear to defend their property which, from an economic point of view, is unproductive. Third is failure to capitalize on gains from trade and exchange, meaning a productive economy requires that assets be used by those who can do so more productively and improvements in property rights facilitate this. Fourth, property supports other transactions. Modern market economies rely on collateral to support a variety of financial market transactions. Secure property rights increase productivity by enhancing such possibilities. De Soto[29] has postulated that formal property rights allowed capital to triumph in the West. People in developing countries accumulate substantial amount of assets but these assets remain dead capital, as they cannot convert their assets to productive capital for want of formal titling and slack enforcement of property rights.

Enforcing property rights and contracts depends upon institutional quality, especially of the courts. Whether the courts have the capacity to decide cases promptly and on merit basically determines the enforceability of property rights and contracts. Our judicial system does little to enforce property rights and rule of law. “It limits access to justice leading to disaffection among the people. Courts are understaffed and judges inadequately trained. Infrastructure is poor. Lack of training of judges and alleged corruption among some of them create endless delays in settlement of cases— Government announced a National Judicial Policy in 2009 with a plan to redress the flaws. There is no review yet.”[30] A flawed judicial system has created distrust, anger, and frustration among the people. According to a report “the lack of justice and public frustration over the existing legal system in Swat Valley contributed to an increase in support for the extremist brand of brutal but decisive law.”[31]

According to Doing Business 2015, on average 46 procedures are involved to enforce contracts and it requires, on average, 993.2 days. Disputes of property drag on for years. Titling of land is a complex issue in Pakistan and lack of clear titles are a big hindrance to realization of the potential of the land. No tangible progress seems to have been made on the front of computerization of land records despite all rhetoric in the last couple of years. “The theories that lay emphasis on encouraging savings to increase growth, assume that savings are converted into investment. The poor implementation of collateral laws and weaker land titles constrain bank lending and therefore investment activity. Therefore the increase in savings per se will not increase investment because legal institutions that are supposed to facilitate the investor are not strong enough.”[32]

(b) Governance and institutional quality

Empirics suggest that good governance is associated with higher growth rates. An ADB study[33] using the World Bank’s worldwide indicators of governance (government effectiveness, political stability, control of corruption, regulatory quality, voice and accountability, and rule of law) has suggested that developing Asian countries possessing a surplus in government effectiveness, regulatory quality and corruption control are observed to have grown faster than those with a deficit in these indicators. Pakistan has consistently fared low against World Bank governance indicators. In 2011, it was ranked 168 out of a total 178 countries. Against the Fragile state index, Pakistan was ranked 13 out of 177 countries in the same year.

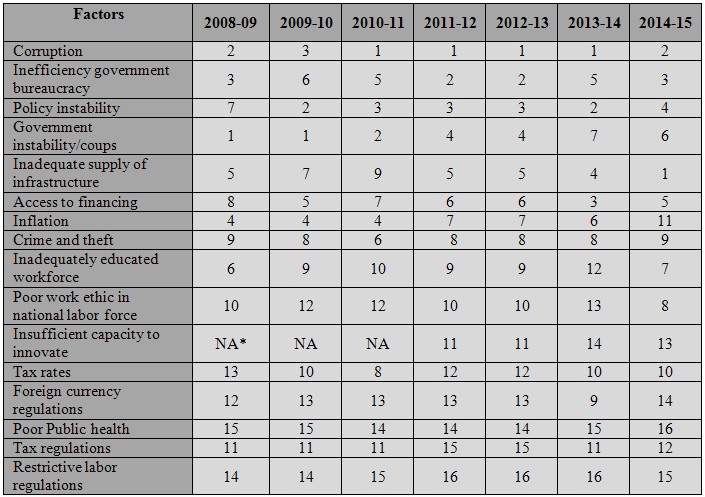

Pakistan is bracketed with countries like Nigeria and Kenya in the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) of Transparency International. As regards to human development, Pakistan is again placed at a low equilibrium of human development as measured annually by the Human Development Index (HDI). Similarly, other reports like Doing Business of the World Bank and WEF’s Global Competitiveness Index, bracket Pakistan with countries earning very low scores. Out of 16 most problematic factors identified by the World Economic Forum’s report each year, corruption and inefficient government bureaucracy are the top most factors in Pakistan. Both the factors are directly linked to bad governance and poor institutional quality. The results of the Investment Climate surveys rate corruption as one of the major obstacles faced by businesses.

Table 11: The Most Problematic Factors for Doing Business

Source: World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Reports for years 2008-9 to 2014-15

* Not available

Pakistan Planning Commission’s, ‘Framework for Economic Growth,’ identifies microeconomic factors related to bad economic governance as the binding constraint for growth[34]. According to the World Bank report[35] “poor governance is a binding constraint to economic growth in Pakistan, with strong distributional and security-related implications. Pakistan ranks among the weakest performing countries on governance indicators worldwide.” Terrorism, a poor law and order situation, political instability, the energy crisis, etc. are all manifestations of poor governance and poor institutional quality. “State has low capacity to enforce the law. Political discourse prefers passion to reason and does little to clarify issues for the citizens. Even on one issue as clear-cut as terrorism, there is no unanimity of view and a fair bit of fudging by some political parties and the media. A clear lack of national purpose along with the level of violence that exists in society precludes the country’s growth in any sector, societal or economic. The result is that Pakistan is a weak state with limited ability to tax, regulate, and protect citizens.”[36] The crisis of growth and poverty is thus rooted to a great extent in institutional decay.[37] This leaves us to speculate that bad governance and poor institutional quality are the binding constraints to economic growth in Pakistan.

Figure 2

Note: By author based on analysis within growth diagnostics framework

From Diagnostics to Therapeutics

The search of constraints to economic growth suggests a short list of binding prime suspects within the framework of growth diagnostics. Access to finance is a constraint not due to high interest rates (real interest rates either in negative or modestly positive) but weak intermediation. Banks are unable to channelize savings, especially of the rural areas, to productive uses. A majority of households are financially excluded. Foreign remittances are, however, on a rise despite economic downturn at the global level. Hence, access to finance as a binding constraint to economic growth is ruled out.

Education though leaves a lot to be desired in terms of access and quality but is not a binding constraint because of the low returns on education in Pakistan. Productivity of the workforce is low due to low skills. Product diversification and export dynamism are lacking due to low productivity and innovation. Structural transformation is also slow. Data from the labour force survey shows that youth labour force aged between 15-29 years in Pakistan was 17.39 million in 2001-02 which increased to 23.75 million by 2012-13, thus registering an increase of 6.36 million. Agriculture is the only sector where youth employment rates have increased. Manufacturing and services sectors have witnessed a decline. The implication is that productivity is on a decline and needs serious focus. Both, the government and the private sector, have an important role to play in this regard. A focus on productivity will be a win-win situation for both.

The government should provide an enabling environment for businesses to grow by enhancing access to quality public goods. The private sector needs to step up and make itself competitive in the changing world and not rely on state protection. Keeping in view the energy shortage and low rate of investment, acceleration of growth can come from higher productivity of factor utilization, i.e. efficient use of capital and labour and other inputs such as water and energy[38]. Both, the public and private sector, have vital roles to play to revive growth and productivity (Box-1). “Entrepreneurship is effectively the willingness and capacity of individuals to take risk in the creation of a business opportunity. This requires an ecosystem that encourages entrepreneurship and innovation through ‘institutional technology’ whereby the institutions, policies, business culture and rule of law provide market dynamics that provide a level playing field”[39]

| Box 1: Focus on Productivity

Markets cannot exist without governments, and vice versa. Governments are essential to the establishment of security, justice, property rights, and contract enforcement, all of which are essential to a market economy. Governments also organize the provision of infrastructure for transportation, communication, energy, water, and waste disposal. They run and regulate health-care systems and primary, secondary, tertiary, and vocational education. They create the rules and provide the certifications that allow firms to assure their customers, workers and neighbors that what they do is safe. They protect creditors and minority shareholders. Saying that governments should get out of the way and let the private sector do its thing is like saying that air traffic controllers should get out of the way and let pilots do their thing. In fact, governments and the private sector need each other, and they need to find better ways to collaborate. The problem is that in many counties, both developed and developing, the current relationship between the private sector and the government is often dysfunctional. Not only is it characterized by deep distrust, but the boarder society does not find a closer relationship to be either legitimate or in the public interest, and for good reason. The private sector often engages with the government in order to make itself more profitable. After all, maximizing profits is what CEOs are supposed to do. And the government has ways to help; it can force suppliers to sell their inputs more cheaply, repress workers wage demands, protect the final market from competition by imports or new entrants, or lower their taxes. But these schemes make firms more profitable by making their suppliers, workers and customers poorer. Accepting such demands makes the government rightly illegitimate in the eyes of the rest of society, which cherishes higher priorities than redistribution in favour of the already rich. Outcomes would be very different if the focus of the relationship were productivity rather than profitability. Productivity improvements, by lowering costs, allow firms to pay their workers and suppliers better, reduce prices for consumers, pay more in taxes, and still make more money for their shareholders. A focus on productivity is win-win-win. The Productivity of Trust by Ricardo Hausmann, Project Syndicate (December 23, 2014) |

In infrastructure, Pakistan fares well compared to its comparators in South Asia. Road, port, and telecommunication infrastructure have improved in the last two decades. Access to electricity, however, is an emerging constraint that is impacting businesses badly. In terms of per capita consumption of electricity, Pakistan is behind its comparators. The problem of electricity shortage is not an infrastructural issue only. It is a governance issue as well.

Tax rates are low compared with its comparators. Customs tariffs have been rationalized. Most industrial raw materials are importable at 5% rate of customs duty. The computerized system introduced a few years back has made trading across borders comparatively easy. Micro risks like corruption, poor law and order, lack of secure property rights, weak enforcement of contracts, a general lack of rule of law, failure to provide effective public services and a lack of or excessive regulations are the first order of concerns for Pakistan. Poor governance due to weak institutions is thus the binding constraint to economic growth in Pakistan.

Structural reforms of a fundamental nature are urgently needed to unleash an entrepreneurial spirit and attract investment in the country. Such reforms should start with revamping of the judicial system. Lack of access, partiality, slowness in decision-making, and corruption weaken enforceability of contracts and property rights. The possibility of establishing commercial courts to adjudicate upon property cases should be seriously explored. The computerization of land records should be a priority to settle disputes of titles.

| Box 2: Structural Reforms Needed

Sustained and inclusive growth requires a number of structural reforms. A national consensus on structural reform is needed to raise productivity and competitiveness and lift constraints on growth. There is little disagreement about the types of reform that are needed, but implementation has been lacking, reflecting a lack of broad political ownership. Improving the reliability and efficiency of Pakistan’s energy supply remains the key priority on the structural reform agenda. Energy reform would also have important complementarities by unburdening the public finances. A strategy is also needed to restructure the large loss-making PSEs. In this connection, a program of divesting public stakes in banks is also necessary to further reduce the state’s footprint in the economy. Then need to improve the investment climate, by promoting better regulation and governance and facilitating the entry and exit of firms, to boost productivity and spur entrepreneurship and innovation. Civil service reform is also necessary to improve the delivery of public services, which is under strain from low tax collection and stepped-up fiscal decentralization. Given the difficult situation in the labor market Pakistan needs sustained and inclusive growth and improved human capital to meet its large employment challenge. Improving the functioning of the financial sector to channel savings to borrowers is also critical, as is raising companies’ access to capital markets. These reforms should be complemented by a further strengthening of the social safety net to support vulnerable parts of the population. IMF Country Report No.12/35 (February, 2012) |

Civil service reforms aimed at making it more specialized, competitive, and responsive is another area. Good governance and better institutional quality hold the biggest promise for growth and development. Moreover, Pakistan does not have the necessary capital and resources to go for the big push. An advisable path would be to go for reforms in the areas where capital is not as essential. We already have some existing structures such as the civil service, the courts, and Police. They are not performing but, if we have the will, we can build on these structures.

Conclusion

Weak governance and institutions undermine all economic activity in Pakistan. Corruption, a slow-moving judicial system, and weak government effectiveness, in particular, add to the cost of doing business and stifle entrepreneurship. We do not need much capital or foreign assistance for improving governance and institutional quality. What we need is political resolve to undertake such reforms and their broader ownership by the elite. However, identification of binding constraints through growth diagnostic analysis is only the first step at looking at what holds back Pakistan from treading the trajectory of sustainable high economic growth. These findings are neither conclusive nor sacrosanct. They are only suggestive in nature.

References & Notes

[*] The author is a graduate from Columbia University. Email: [email protected]

[1] J.R Lopez-Calix,T.G Srinivasan and M. Waheed, “ What do we know about growth patterns in Pakistan?”, World Bank Policy Paper series , Dec,2012

[2] Economists also call it ‘ a measure of our ignorance’

[3] Growth paths: country specificity in practice, country note for growth diagnostic studies, PREM, World Bank

[4] Ricardo Hausmann, Dani Rodrik,and Andres Velassco, ‘ Growth diagnostics’, working paper available at http:/ksghome.harvard.edu

[5] Ricardo Hausmann, Bailey Kalinger, and Rodrigo Wagner, “ Doing growth diagnostics in practice: A ‘ Mindbook’ , Center for International Development , Harvard University

[6] Dani Rodrik, “ Diagnostics before prescription”, The Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol.24,No.3 (Summer 2010)

[7] Jesus Felipe and Norio Usui , “ Rethinking the growth diagnostics approach: questions from the practitioners” ,ADB working Paper series, Asian Development Bank, Manila, Nov,2008

[8] Economic Survey of Pakistan,2013-14 , Ministry of Finance, Pakistan

[9] IPR Six Monthly Review 2014-15 ( March 5,2015)

[10] Financial inclusion is a process that ensures the ease of access, availability, and usage of financial services for all members of the society. Accessibility, availability, and usage are thus the important ingredients of financial inclusion.

[11] End extreme poverty? Let’s start with financial access for all ( blog February,2015)

[12] Ehsan U .Choudri and Hamza Malik, “Monetary Policy in Pakistan: confronting fiscal dominance and imperfect credibility”. International Growth Center (Dec2012)

[13] Mahmood ul Hassan Khan & Bilal Khan, “What drives interest rate spreads of commercial banks in Pakistan? Empirical evidence based on panel data”, SBP Research Bulletin, 2010

[14] IPR Six Monthly Review 2014-15 ( March 5,2015)

[15] Tatiana Nenova, Cecil Thioro Niang & Anjum Ahmad, “ Bringing finance to Pakistan’s poor: A study on access to finance for the undeserved and small enterprises”, World Bank (May,2009)

[16] Abdul Qayyum, Idrees Khawaja & Asma Hyder, “ Growth diagnostics in Pakistan”, European Journal of Scientific Research Vol.24 No.3 (2008)

[17] Economic Review 2013-14 and Economic Outlook for 2014-15, IPR ( August,2014)

[18] Jose Lopez-Calix & Irum Touqeer, “ Revisiting the constraints to Pakistan’s growth”, Policy Paper series on Pakistan , The World Bank ( June, 2013)

[19] Jeffrey D. Sachs , “ Tropical Underdevelopment”, NBER Working paper (2001)

[20] Jared Diamond, ‘ Guns, Germs and Steel’, Vintage Books, London ,2005 Edition

[21] Jose Lopez-Calix & Irum Touqeer ibid

[22] Pakistan—Finding the path to job –enhancing growth, The World Bank , 2013

[23] National Power Policy, Government of Pakistan,2013 ( page 5)

[24] Addressing Inequality in South Asia, World Bank’s Report, 2015

[25] The World Bank 2013 ibid

[26] A net creation or destruction of exported items is considered a proxy for export dynamism. A net positive creation i.e. number of creation minus the number of destruction of exported items, is indicative of export dynamism. In case of Pakistan, we do not see much increase in the number of exported items which are yet concentrated in few sectors.

[27] The world Bank 2013 ibid

[28] Tim Besley & Maitreesh Ghatak, “ Reforming property rights”, VOX, CEPR’s Policy Portal ( April 22,2009)

[29] “The Mystery of Capital: Why capital triumphs in the West and fails everywhere else”, Basic Books Hardcover Edition (2000)

[30] IPR report on governance, 2014

[31] Pakistan 2020, A Vision for Building a Better Future, Asia Society Pakistan 2020 Study Group Report, p. 22.

[32] Abdul Qayyum et al 2008

[33] Xuehui Han, Haider Khan & Juzhong Zhuang, “Do governance indicators explain development performance? A cross-country analysis”, ADB Economic Working Paper Series (2014)

[34] Pakistan: Framework for economic growth , Planning Commission ( May 2011)

[35] The World Bank 2013 ibid

[36] IPR ibid

[37] Akmal Hussain , ‘ Institutions, economic structure and poverty in Pakistan’, South Asian Economic Journal (2004)

[38] The state of economy: from survival to revival, Institute of Public Policy , Beaconhouse National university ,Lahore ( Sixth Annual Report, 2013)

[39] New Growth Models: challenges and steps to achieving patterns of more equitable, inclusive and sustainable growth, World Economic Forum ( January, 2014)