By

Jamil Nasir[1]

Abstract

This paper analyses the changing paradigms of economic inequality and the baneful effects it can have on economic growth, development of institutions and financial, political and economic stability, subjective wellbeing, etc. After analyzing inequality purely from an economic perspective, the paper takes stock of inequality in Pakistan. The factors responsible for extreme inequality in Pakistan are almost structural in nature. Skewed distribution of productive assets, an ineffective taxation system, rent seeking, unequal opportunities of education, and regional disparities due to urban- biased public policies have been identified as the main drivers of inequality. This paper gives two sets of recommendations i.e. revolutionary (the high road) and evolutionary (the low road) for addressing the problem of economic inequality in Pakistan. It concludes that status quo is not an option anymore as frustration of the people with the system is fast increasing. Author)

Introduction

(a) Inequality-development nexus

Inequality has come under renewed focus in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. Historically, inequality was seen more of an ethical issue. Economists were more concerned about output, GDP, growth, savings, investment, etc. Traditional economic thinking was that increasing the pie was the real issue. Its distribution was not that important. Rather, inequality was considered the handmaiden of development. The development-inequality relationship was postulated by Simon Kuznets back in the 1950s. He described the relationship between inequality and prosperity as an inverted U, meaning thereby that inequality first rises during the early stages of development, reaches a peak, and then declines. However, during the last 30 years inequality has risen globally and, as mentioned in The Economist in one of its reports on this subject, ‘the inverted U has turned into something closer to an italicized N, with the final stroke pointing menacingly upwards.’

The inverted U relationship gave two lines of argument. The first line of argument was that there is a natural tendency for inequality to increase in the early stages of development, so policy interventions were needed to mitigate its negative consequences. The second line of argument said that since inequality would eventually decrease, it was worth waiting out the initial increase as policy tinkering to hold back the initial inequality increase via redistribution could dampen economic growth. Moreover, doing so just meant the postponement of the turning point of the inverted U.1 So the standard thinking of the classical economists was that development was essentially inegalitarian.

Lewis Arthur wrote2 in 1976, “Development must be inegalitarian because it does not start in every part of the economy at the same time. — There may be one such enclave in an economy, or several; but at the start development enclaves include only a small minority of the population.” So the point in a nutshell is that traditional economic thinking was that inequality is a necessary outcome of initial stages of development though it recedes later in the development process. The evidence is, however, mixed on the shape of the inequality-development association. It is not necessarily always an inverse U relationship and inequality does not necessarily decline even at the advanced stages of development.

(b) Kuznets curve and dualism of economy

According to a latest study3, based on longitudinal data of 26 countries covering the period 1900-2010, the inequality-development relationship even turns positive at the higher levels of economic development. Another interesting point relating to Kuznets curve is what factors make the fall of Kuznets curve in the advanced stages of development. According to the dualistic model of economy developed by Lewis Arthur, the narrowing of gap between incomes of agriculture and non-agriculture is one of the most powerful forces in mitigating inequality at the developed stages of the economy. The narrowing of gap between the agriculture and non-agriculture sector can occur mainly due to two reasons.4 First, policy interventions like investments in physical, human, and social capital in a lagging sector can pull up the income of that sector. Second, movement of labour from agriculture to industry would eventually create shortage in agriculture as a result of which wages would increase in that sector simply due to forces of demand and supply.

When a society undergoes metamorphosis from an agrarian to an industrial economy, there are both losers and gainers. Industrialists and the middle classes gain while in a world of ‘mechanization and desperation’, the laborers work only for subsistence wages in the initial stages of industrialization. They live in pitiable conditions as depicted vividly by Charles Dickens in his novel ‘Hard Times’. Once industrialization becomes the dominant mode of economy, pressure mounts for increase in wages as labourers start organizing themselves.

Literature on inequality recognizes at least three channels through which inequality can impact political outcomes.5 First, inequality leads to desire for redistribution. Second, higher inequality might reduce redistribution and provision of public goods as economic resources not only determine preferences but ability to influence political outcomes as well. Third, economic inequality might influence the whole structure of political institutions.

(c) Political economy of Kuznets curve

According to political economists, decrease in inequality is not automatic. Redistribution of resources and decline in inequality depend on the power structures and arrangements in society. If a real democracy is lacking, it will simply be a case of ‘elite capture’. The elite will be more interested in perpetuating their hegemony over power and resources. Political reforms or wide sharing of power will be possible only if there is a threat of revolution or change of status quo which in turn requires that the civil society is vibrant and coherent in its demands. Further, people are least polarized on ethnic, linguistic, biradari or geographical lines.

If they are voiceless and do not feel empowered to change their destiny either through ballot (democracy) or threat of a bullet (constant pressure on the elite for reforms to avert bloody revolution), such a society will experience high inequality and redistribution of resources will be weak as is clearly the case of Pakistan. Professor Daron Acemoglu et al6 argue that decline in inequality, as postulated by economists like Simon Kuznets and Arthur Lewis, is not automatic and merely structural changes in the economy do not guarantee that inequality will eventually decline in the advanced stages of development.

They wrote: “The historical and contemporary evidence suggests that the downward segment of the curve is driven by political reforms and their subsequent impact. In turn, these political changes are induced by the rising social tension and political instability that arises from the increased inequality on the upward segment of the curve. Nevertheless, as the empirical evidence has established, such a curve does not characterize all development paths. Our model suggests two circumstances where development would not induce a Kuznets curve. Firstly, if inequality is very low initially so that all agents could invest, development could occur without heightened tensions and political reform could be avoided.

In this part of the parameter, space, a country would experience rapid economic development without growing inequality or political reforms.

We argued that this situation captures well some of the post World War II growth experiences in East Asia. Secondly, when civil society is very unmobilized even widening inequality may not be sufficient to force political reform. Such a country experiences increasing inequality, poor growth, and no political reform.” Even rise of inequality in the early stages of development is not inevitable. The development experience of East Asian countries is a big exception. The mass land reforms that took place in the late 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s fundamentally altered the subsequent relationship between inequality and growth.

Perfect equality has never been an ideal with the economists as unequal rewards incentivize people to put in greater effort and risk-taking. Rather, inequality was considered desirable by them. They are comfortable even now with ‘meritocratic inequality’, though meritocracy itself in an unequal society becomes a farce. It is now widely believed that inequalities of income and assets have serious harmful effects.

Extreme inequalities are not only despicable from a moral perspective but the economic case also is equally strong against extreme inequalities of income, assets, and influence.

Economic costs of inequality

(a) Inequality reduces economic growth:

The conventional economic thinking was that the rich saved more, so inequality did not matter much from an economic perspective. The only concern with regard to extreme inequality in a society was that it induced a threat of massive redistribution which could undermine economic growth. And investors could feel uneasy about a nation’s future due to fear of redistribution and expropriation. In a highly unequal society, the fear of confiscatory taxes, expropriation, or nationalization always lurk in the minds of the investors as the have-nots, being in a majority, could, at any time, win a political struggle. The conventional economic thinking premised on the assumption that the rich saved more, hence invested more and resultantly savings and investment guaranteed economic growth. Such a model of growth is now facing serious challenge, especially in the wake of persistent low growth in USA and Europe. It is being argued that extreme inequalities dampen growth by reducing aggregate demand. If income and wealth are concentrated in the thin minority at the top, spending will be low and hence aggregate demand will be low, as the rich tend to spend a smaller fraction of their income than the poor, and consequently economic growth will be low.

Low spending means low aggregate demand and in simple words, closure of factories and businesses and unemployment. On the other hand if income is widely distributed in society, aggregate demand will be high due to high spending and hence economic growth will be high. Besides ‘how much you spend’ i.e. quantum and ‘where you spend’ i.e. composition also has implications for aggregate demand. For example, the middle class will spend most of their income on food, schooling, health, and purchase of household effects and such expenditures will create sufficient demand. Consequently, factories and businesses will flourish and jobs will be created. Thus a positive cycle of more spending, more demand, more employment generation, more income and resultantly more spending is established.

The rich generally spend on palatial buildings, diamonds, jewelry and other luxury things which in a sense are static assets. Such capital generally remains dead for a long time and does not trigger a stream of consumption and investment. Joseph Stiglitz writes,7 “Moving money from the bottom to the top lowers consumption because higher-income individuals consume a smaller proportion of their income than do lower-income individuals. The result: until and unless something else happens, such as an increase in investment or exports, total demand in the economy will be less than what the economy is capable of supplying—and that means that there will be unemployment.”

Second, squeezing the incomes of the middle class means that they are unable to invest in the future. They are unable to invest in the education of their children. They are unable to invest in improving their existing businesses or initiating new ones. Third, inequality, according to Professor Stiglitz, is also associated with boom-bust cycles as economic inequality and economic instability are closely intertwined. There are other channels as well through which extreme inequality tends to reduce economic growth. For example, much of the economic inequality in the entire world is associated with rent-seeking8 such as monopoly power and economists tell us that rent-seeking undermines economic efficiency. People who are lower on the socioeconomic ladder in highly unequal societies have shorter and less healthy lives.9

So, economic inequalities are linked with health inequalities. Better health of the workforce is considered one of the important ingredients of national competitiveness of a country. More equal societies have better health outcomes. In countries like Sweden and Norway, even the poorest and most vulnerable groups live longer than their counterparts in countries like UK and USA.10 High income inequality also negatively impacts the performance of the students. Empirics11 suggest that even in a developed country like USA, there is a causal relationship between income inequality and high drop-out rates among disadvantaged youth.

Individuals’ perceptions of their own identity, their relative societal position, perceived chances of their success, and economic despair may be some of the plausible reasons for high dropout rates among the low income school students.

Traditional economic thinking on the redistribution-growth nexus was that it affected economic growth negatively. This thinking is now changing. According to one of the latest papers12 of IMF, it is a mistake to focus on growth and let equality take care of itself. If we do not take care of inequality, the resulting growth may be low and unsustainable. Moreover, there is little evidence for the growth-destroying effects of fiscal redistribution at the macroeconomic level. Then why is there confusion about the role of redistribution? In addition, the paper says, “The evidence on the relationship between inequality and redistributive transfers is not clear cut, but part of the ambiguity stems from the fact that many studies assess imperfect proxies for redistribution, such as social spending and tax rates. While we may think of some categories of spending as redistributive (such as education and social insurance spending), they need not be redistributive in practice. Consider spending on post-secondary education in poor countries or on social protection for formal sector workers in many developing countries.” So the point is that extreme inequality is not only repugnant from the moral perspective but it is bad economics as well.

(b) Inequality undermines institutions

Inequality shapes economic and social outcomes. “Inequality enables the rich to subvert the political, regulatory, and legal institutions of society for their own benefit. If one person is sufficiently richer than other, the courts are corruptible; then the legal system will favour the rich, not the just. Likewise if political and regulatory institutions can be moved by wealth or influence, they will favour the established, not the efficient.”13 There can be several ways through which inequality can undermine institutions.

First, it may endanger security of property rights. Security of property rights is considered sine qua non for growth by the economists and proponents of capitalism. The argument runs that the have-nots can redistribute resources from the haves either through violence or political process. Such ‘Robin Hood Redistribution’ jeopardizes property rights and negatively affects investment. Second, the haves can subvert legal, political, and regulatory institutions to make them work in their favour. It will be a type of ‘King John Redistribution’ which can make the property rights of the small entrepreneurs insecure. Third, inequality corrupts democratic governance. In a comparatively more equal society, it is difficult for an individual to buy public officials or agencies but in an unequal society, it is easy for the rich to buy political influence and bend the policies and rules in his favour. Due to rising inequalities in Western Europe and the USA, even democracy as a system of governance is now being questioned.

Stiglitz writes,14 “If economic power in a country becomes too unevenly distributed, political consequences will follow. While we typically think of the rule of law as being designed to protect the weak against the strong, and ordinary citizens against the privileged, those with wealth will use their political power to shape the rule of law to provide a framework within which they can exploit others. They will use their political power, too, to ensure the preservation of inequalities rather than the attainment of more egalitarianism and more just economy and society. If certain groups control the political process, they will use it to design an economic system that favors them.” Inequality also affects the ability of the people to act collectively. It also impacts the ways institutions are set up in society and resources are allocated for various groups. Provision of public goods is a case in point.

“On the one hand, in a very unequal society, the better off typically have more power and are more effective at pulling in resources for the public goods they value. On the other hand, a high degree of inequality makes it more tempting for the better-off to opt out of public services altogether. In the end, which of the two effects prevails is likely to depend on whether opting out is an option”15. Oxfam’s report16 says, “When those at the top buy their education and health services individually and privately, for example, they have less of a stake in the public provision of such services to the wider population. In Pakistan, the number of private schools increased by 69% between 2000 and 2008. When wealthier people do not use public services, they also feel less incentive to pay their taxes, threatening in turn the financial sustainability of these services.”

(c) Inequality increases crime

The standard economic thinking is that crime is higher in more unequal societies. The economic theory of crime views the decision to commit crime as a rational decision like all other economic decisions.

For example, the decision to steal involves a choice between two alternatives of generating income i.e. either one can invest time in lawful production or in appropriating the property of others. As inequality rises, the returns to crime increase for the poor because rich victims are richer, and the opportunity costs of the crime are lower because the poor are the poorer. Moreover, inequality may negatively impact the level of policing. Inequality may also dilute the deterrent effect of legal sanctions as life in prison may sometimes be better than life out of prison17. Oxfam’s report18 says, “Homicide rates are almost four times higher in countries with extreme economic inequality than in more equal nations. Latin America—the most unequal and insecure region in the world—-starkly illustrates this trend. It has 41 of the world’s 50 most dangerous cities, and saw a million murders take place between 2000 and 2010. Unequal countries are dangerous places to live in.”

(d) Inequality undermines stability

Stagnant wages or decreasing wage rates are the real issue for an economy as low wages simply mean insufficient aggregate demand. Insufficient consumption demand can be dealt with in three ways. First, the system rebalances itself by shifting production towards investment goods. If this rebalancing happens, lack of consumption demand can be compensated by higher investment demand. Second, the income earned by the wealthy (say top 1 %) can be spent on investment in the form of financial assets. If the income of the majority stagnates or declines, consumption levels are not adjusted immediately and as a consequence household debts rise. The third option is finding demand for the goods and services outside the country, meaning that surplus goods and services can be exported and income can be spent for buying financial assets abroad. For a country facing insufficient demand or excess savings over investments, this opens up the possibility to sustain high production levels at least for some time but it may not be an option for all the countries.19

Mr. Kemal Dervis rightly points out that: “macroeconomic policy can try to compensate the excess of planned savings over investment through deficit spending and very low interest rates. Or an undervalued exchange rate can help to export the lack of domestic demand. But if the share of the highest income groups keeps rising, the problem will remain chronic. And, at some point, when public debt has become too large to allow continued deficit spending, or when interest rates are close to zero bound, the system runs out of solutions.”20

Inequality can destroy political stability and social cohesion. It can spark social and political tensions in the country. ‘Wealthification of politics’ eventually undermines democracy by giving the wealthy inadequate influence on political decisions. Economic equality provides legitimacy to the state. “Economic equality is the foundation of social solidarity (generalized trust) and trust in government. Generalized trust leads to greater investment in policies that have longer term payoffs as well as more directly leading to economic growth. A weak state with an ineffective legal system cannot enforce contracts; a government that cannot produce economic growth and the promise of a brighter future will not be legitimate. Unequal wealth leads people to feel less constrained about cheating others. Inequality leads to unequal treatment by the courts, which leads to less legitimacy for the government.”21 Extreme inequalities threaten society. The World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Survey has consistently included deep income inequalities in its last three surveys as one of the top risks the world would be confronted with in the coming decade.

(e) Inequality reduces happiness

Acute inequalities reduce happiness. Initially, the economists thought that inequality was the very basis of diversification in society.

It incentivized people to work hard and achievement gave a sense of satisfaction and success, hence it was happiness-enhancing. However, it is now being argued that inequalities in the society reduce happiness because happiness levels in a society are determined more by the relative income than by absolute income. Professor Robert Skidelsky says: “We constantly compare our lot with that of others, feeling either superior or inferior, whatever our income level; well-being depends more on how the fruits of growth are distributed than on their absolute amount. Put another way, what matters for life satisfaction is the growth not of mean income but of median income—-the income of the typical person.”22

Creation of a happy society requires bridging of the gulf between the rich and the poor. A big palatial house standing out in many small houses scattered around undermines happiness of those who live in the small houses. Ostentatious living, display of wealth (often gotten through rent-seeking and corruption) and the perverted values which employ such behaviors as measure of status and prestige further deteriorate happiness of the people in a society. Wealth if legally earned is not bad. What kills happiness is its undue and ostentatious display. Extravagant spending on marriages, building of palatial houses, big cars, and protocol systems are some of the demonstrations of ostentatious display of wealth in our society. If economic disparities are low in a society, wellbeing can be higher, even in low income economy. The experience of the state of Kerala in India vindicates this assertion.

Literature on happiness emphasizes that once people achieve a certain level of income which is sufficient to meet their basic needs, any increase in income does not significantly contribute to achieving further happiness. The notion that money and happiness are positively correlated all along the way is certainly based on a mistaken belief. Professor Richard A. Easterlin (known for the Easterlin paradox) also affirms this idea. Public policies should be aimed at providing better health and education facilities, speedy justice, reducing corruption and narrowing the gap between the rich and the poor. Such public policies will bring happiness through minimizing inequality and unfairness, the two major causes of unhappiness.

(f) Inequality impedes poverty reduction

According to Oxfam, extreme inequality is a big stumbling block to poverty alleviation in the world. If India is able to stop inequality from rising, it could end extreme poverty for 90 million people by 2019 and millions more could be lifted out of poverty in Kenya, Indonesia, and India if income inequality were reduced. “Income distribution in a country has a significant impact on the life chances of its people. Bangladesh and Nigeria, for instance, have similar average incomes. Nigeria is only slightly richer, but it is far less equal. The result is that a child born in Nigeria is three times more likely to die before his/her fifth birthday than a child in Bangladesh.”23

Inequalities deepen poverty in a society. Empirics24 based on micro-census data from the US, covering the period 1960-2010, suggest that high levels of inequality reduce the income growth of the poor and help the growth of the rich. The analysis shows that it is mostly the inequality at the top which is holding back the growth at the bottom. Milanovic et al suggest that one plausible explanation of this observation is that high levels of top inequality serve as a proxy for ‘social separatism’ where the rich lobby for policies for their benefit which eventually limit the growth opportunities of the poor.

It is in the context of heightened realization regarding baneful effects of economic inequality that demand is now growing to make inequality reduction a sustainable development goal in Post-2015 i.e. after the sunset of the current millennium development goals (MDGs).

A group of 90 economists, academics and development experts have demanded that inequality reduction should be at the heart of the post-2015 development framework. Well respected economists like Professor Jose Antonio Ocampo, Jayati Ghosh, Andy Sumner, Sir Richard Jolly, Indu Bhushan, Dr.K.Parbharkar, etc. in a letter to Dr Homi Kharas of Brookings Institute who is associated with the post-2015 Development Agenda have emphasized that “a core objective of the post-2015 framework must be to enshrine our joint responsibility to tackle inequality at many different levels”. Professor Joseph Stiglitz who has long been talking about the baneful effects of inequality on economic growth and development is supporting the idea that inequality reduction should become a sustainable goal (9th SDG) in the post-2015 development framework.25

Some pertinent questions, however, are: What should be the achievable targets for this goal? What should be the parameter to monitor the progress on this goal if the world agrees to adopt it as a sustainable development goal? Thus if reduction of inequality is adopted as post-

2015 goal, the Palma ratio of one can be set as a target for the member countries of the UN. To achieve this goal, Professor Stiglitz proposes the targets as follows: (1) Reduce extreme income inequalities by 2030 in all countries with a view to achieve Palma ratio of one, meaning thereby that income of top 10 % is no more than the income of the bottom 40%;

(2) Establish a public commission by 2020 in every country to assess the effects of national inequalities.

Measurement of Inequality

(a) Need to put the Gini back in the bottle

Traditionally the Gini Index is used for determining how unequal a society is. Its value ranges between zero and one. A value of zero means that income is uniformly distributed among all the citizens of a country. If the value of Gini is one, it means that one person in that society owns all the income. But no nation has ever had either absolute income equality or absolute income concentration. Every country ends up with some number between zero and one. If the Gini of country A is 0.45 and country B‘s Gini is 0.5, it means that country B is more unequal compared to country A.

Moreover, say in year 1 the Gini is 0.45 which increases to 0.47 in year 2, what does it tell? It tells only that distribution of income has become more unequal in year 2 but it does not offer any clue about the drivers of such change. Are the rich getting more or are the poor losing ground or are income changes taking place in middle-income households? So the Gini Index does not provide a better yardstick for the measurement of inequality at least for policy makers.

(b) Virtues of Palma

Professor Stiglitz has thus recommended that ‘Palma ratio’ should be used instead of the Gini index for monitoring progress on the proposed goal. It has been argued and rightly so that Palma ratio is a more policy-relevant measure of inequality26 because given the stability of the middle class, it is very much clear what needs to be changed. The Palma is based on the work of Gabriel Palma, a Chilean economist, currently working as senior lecturer at Cambridge University. Gabriel Palma analyzed data of a number of countries and observed that half of the gross national income of a country in almost every case is captured by the middle class while the remaining half is distributed among the top 10 % (the rich class) and the bottom 40% (the extremely poor).

Distributional politics is concerned entirely with how the 50% is divided between the rich (top 10%) and the extremely poor (bottom 40%) while the share of the middle class remains stable (deciles5-9).27

The beauty of the Palma ratio is that it captures the two extremes of inequality as it is a ratio between the top 10% incomes and the bottom 40%. Thus the extreme inequality resides in the tails. “It is Palma’s simplicity which we would argue is its greatest strength. A Gini coefficient of 0.5 implies serious inequality but yields no intuitive statement for a non-technical audience. In contrast, the equivalent Palma of 5.0 can be directly translated that the richest 10% earn five times the income of the poorest 40% of the nation.”28 There is now talk of Palma version 2 and Palma version 3.

For example, Alice Krozer29 has found out that traditional indicators of inequality are less sensitive to the changes at the extremes of the income distribution. The income share of the top 5% to bottom 40% called Palma v.2 could act as a complementary indicator for the measurement of inequality to avoid the obscurity of measurement. While emphasizing the Palma ratio, Stiglitz writes: “All countries should focus on their extreme inequalities, that is, the inequalities that do most harm to equitable and sustainable economic growth and that undermine social and political stability. A Palma ratio of one is an ideal reached in only few countries. For example, countries in Scandinavia, with Palma ratios of one or less do not seem to suffer from the liabilities associated with extreme inequalities”.

Inequality in Pakistan

According to a latest study30 of Oxfam on inequality in Pakistan, children born in income–poor families in Pakistan in the year 2010-2011 are less likely than those born in the year 1994-1995 to break the poverty trap and move to the middle class category. About 40% of the sons born to the father belonging to the bottom quintile remain in the bottom quintile; only 9% make it to the top quintile while 52 % sons born to the rich remain rich. The finding of the study is that inequality traps in Pakistan are deepening. To make this point, the report identifies four peculiarities of inequality traps. First, a majority of the sons of poor fathers remain poor and a majority of the sons of rich fathers stay rich. Second, the educational gap between the rich and the poor is increasing.

Third, sons follow fathers in the choice of occupations and fourth, girls are discriminated against in terms of educational expenditure and choice of occupation.

What does this low social mobility imply? It simply means that income disparities in our society are very deep. Highly unequal societies tend to have low social mobility—a relationship popularized by Alan Krueger as the ‘Great Gatsby Curve’. Had there been equality of opportunity, then we should have observed high mobility in Pakistan.

Miles Corak31 observes: “In countries like Finland, Norway and Denmark the tie between parental economic status and the adult earnings of children is the weakest: less than one-fifth of any economic advantage or disadvantage that a father may have had in his time is passed on to a son in adulthood”,

Recent studies32 based on income data suggest that income distribution in Pakistan has worsened. Given the poor quality of data, it would not be fair to conclude that accounts of inequality give a perfect or even fair assessment of changes in income inequality in Pakistan.

However, two recent research reports, one by Oxfam33 and the other by SPDC34, give a more detailed account of the changes in inequality in Pakistan and the ensuing discussion (in the proceeding few paragraphs) is based on the data/information mentioned in these reports.

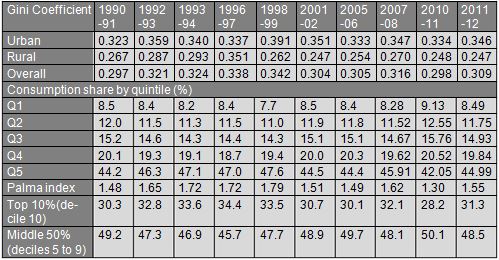

According to the Oxfam report, the consumption share analysis by quintile shows that the consumption share of the poorest 20% of the population witnessed significant decline in the 1990s. In this period the consumption share of the middle 60% of the population also declined while the share of the richest 20% increased significantly. The consumption share of the richest 20% was more than five times the share of the bottom 20%. This ratio peaked at 6.18 in 1998-99 confirming worsening of income distribution across groups in the 1990s. According to the report, “Growing inequality of income was reflected in the form of joblessness, household deprivation, economic and social polarization and the alienation of the general public from politics and politicians.” Changes in income inequality in Pakistan during the period 1990-91 to 2011-12 are given in the table below.

Table 1

Changes in inequality

Source: Multiple Inequalities and Policies to mitigate inequality traps in Pakistan by Abid

A. Burki et al,

Oxfam Research Report, 2015

It is also evident from the above tabulated information that the Palma index continued to increase in the 1990s due to worsening of income distribution. The share of the richest decile (decile 10) increased while those of the poorest deciles (1-4) decreased. The rise in inequality and poverty during this era can partly be attributed to policies like public sector wage freezes, ban on public sector employment, and public sector spending cuts pursued to meet IMF conditionality.35

This trend declined only to return with a sharp rise in the Palma Index during 2011-12 when it reached 1.55, above the years 1990-91 (1.48) and 2001-02 (1.51). According to the Oxfam report: “Post 1998-99 gains in income distribution may be attributed to a high growth period in the country from 2001-02 to 2007-08, lower inflation and more job creation in the manufacturing and services sector.” Oxfam’s report finds that time profile of Gini coefficient by region shows that levels of urban inequality are much higher compared to rural areas. The plausible reasons, according to the report, are: (a) urban workers are much more diversified whereas rural households possess uniform skill-sets (b) the bulk of land owners are small or very small resulting in comparatively even distribution of incomes.

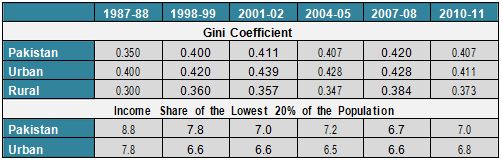

The SPDC report finds that rural income inequality has increased more severely from 1987-88 to 2010-11 than urban equality (73 versus 11 basis points), as is evident from Table2 below.

Table 2

Source: Growth and Income Inequality Effects on Poverty (Research Report No.94), 2015

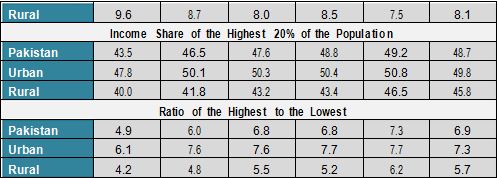

The SPDC report states that, “Persistent low growth during the period 1987-1999 resulted in significant deterioration in the income distribution as measured by inequality measures. On the contrary in the high growth episode (2001-05), an improvement of about 10 basis points is observed in both urban and rural income Gini coefficients. A significant deterioration in rural income inequality is also observed during the period 2005-2011.” Regional analysis shows that income inequality has deteriorated in three provinces from 1990-91 to 2011-12.

Baluchistan is the only province where we see some decrease in income inequality during this period (Table3).

Table 3

Gini Coefficient by Province

Source: Multiple Inequalities and Policies to mitigate inequality traps in Pakistan by Abid

A. Burki et al, Oxfam Research Report, 2015

Drivers of inequality in Pakistan

Rising wage differentials, low progressivity of taxation, rent-seeking, winners take all culture assisted by globalization, technology (race between skills and technology), and social changes (like more people marrying with a partner in the same earnings group) are considered some of the top culprits for the rise in inequality in the USA and OECD countries. Recently, Professor Picketty36 has suggested that inequality is inherent in the nature of capital. His argument is that market capitalism will eventually lead to an economy dominated by the lucky ones born into a position of inherited wealth as the rate of return on capital has historically remained higher than the rate of growth and if rate of return r exceeds rate of growth of the economy i.e. r>g, the share of capital income in the net product will rise.

It has also been argued that the share of labour has decreased in the total income of the developed countries which simply means that the major share of national income has gone to the capitalists. Certainly, the rise in the share of capital has contributed to greater inequality but changes in the earnings of labour are also responsible for the increase in inequality as incomes of high skilled labour have increased manifold relative to the earnings of low-skilled workers. These factors may not apply in case of Pakistan. In our case factors responsible for deep-rooted inequality are mainly structural in nature which can broadly be divided into five categories.

(a) Skewed concentration of productive assets

Land is traditionally considered the most productive asset but the Gini Coefficient of land in case of Pakistan is very high. Land ownership inequality is highest in Punjab followed by KP, Sindh and Baluchistan. Half-hearted efforts at land reforms in the past failed to change the economic and political landscape of rural areas. Highly skewed distribution of land has serious implications for egalitarianism in society. Empirical evidence suggests37 a deep nexus between land and power. Skewed ownership of land results in strong patron-client relationships where the employers i.e. landlords concede some rents to the landless and threat of withdrawal of such rents influences political preferences. Thus land not only creates economic inequality, it also results in inequalities of power.

According to some estimates, about 67 % of households in the rural areas of Pakistan do not own any land. About 18% of the households own less than 5 acres of land and about 10% own 5 to 12.5 acres of land, which is merely a subsistence level. Only 1% of the households own more than 35 acres of land. Added to this, changes in agricultural practices (mechanization of farming), low quality fertilizers and pesticides due to poor governance, and policy neglect of non-farm rural economy have further deepened inequality and poverty in the rural areas. And unless serious reforms are introduced, it would be hard to arrest the rise in rural inequality but the point is whether the landed elite would let such reforms take place. John McDermott is perhaps right when he says in one of his articles38 that: “Inequalities of power have their own dynamic. For the greater the gains to being part of an elite, the more those currently at the top will fight to stay there.

(b) Ineffective taxation System

The second broad source of inequality in Pakistan is an ineffective taxation system which is hardly progressive. All types of income are not taxed and exemptions are many. A majority of the potential taxpayers are out of the tax net. The major focus of the taxation system is on indirect taxes that are regressive in nature. The Oxfam report says that, “The regressive nature of the taxation system is a reflection of how Pakistan’s elite have consolidated their bargain with the state—– for example agriculture contributes 20% to GDP but just 1 % to taxation. The services sector contributes 50% to GDP but only 30% to taxation. The wholesale and retail sub-sectors contribute about 19% of GDP but just 0.5 % to taxation.”

The current taxation system is contributing towards inequality, at least, from three angles. One, the government is unable to collect sufficient money to invest in inequality-reducing projects like quality education and healthcare. Two, incomes and wealth of tax evaders are persistently rising due to rampant tax evasion. Three, the government is constrained to borrow due to low domestic revenue mobilization and such funding comes with strings. Austerity is invariably a condition attached with the loans. Due to a highly inflexible public expenditure structure, the hammer of austerity always falls on social spending.

The Tax Directory of 2014 shows that only 40% of the companies registered with SECP filed returns, what to say of individuals. Tax evasion is so rampant that even public figures do not pay their due taxes due to weak capacity of the state and lack of political will. A senior journalist who has worked on the tax returns of the Parliamentarians says, “Under every stone is a story on how people find ways, mind you through legal loopholes, to wiggle out of paying taxes. It does not require a rocket science to see the lifestyle they maintain and the paltry sum they pay as tax.”

(c) Rent-Seeking

The third source of inequality in Pakistan is rampant rent-seeking in society. What do we mean by rent seeking? “People are said to seek rents when they try to obtain benefits for themselves through the political arena. They typically do so by getting a subsidy for a good they produce, or for being in particular class of people, by getting a tariff on a good they produce, or by getting a special regulation that hampers their competitors”39. Countries where rent seeking, such as easy corruption, poor laws, and permissive legal systems, is rampant can suffer economically for at least two reasons.40 First, rent-seeking activity has increasing returns which means that very high levels of rent-seeking may be self-sustaining which is economically inefficient. Second, public rent-seeking stifles innovation and consequently reduces economic growth.

Permits, quotas, licenses, SROs, outright bribery and corruption have created a class of rent-seekers. Ours is a rent-seeking, elitist state where feudal landholdings are intact due to ineffective land reforms. The industrial elite have emerged as a result of a licence raj and SRO culture. The wealth accumulated through rent-seeking is used to grab political power to influence public policies. Due to the capture of resources by the elite, social mobility is severely restricted in Pakistan. A symbiotic relationship is very much visible in the country where the elite have forged an unholy alliance to extract rents through interplay of political and economic power.

(d) Unequal opportunities of education

Unequal opportunities in educational attainment are the fourth broad reason behind income inequalities in Pakistan. The constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan promises education as a fundamental right and the 16th Amendment to the constitution assures free and compulsory education to all children up to 16 years of age. Despite these constitutional guarantees, the number of out-of-school children in Pakistan is the second highest in the world. About 25 million boys and girls within the age-bracket of 5-16 are out of school. Besides the issues of coverage and access, quality issues are very serious. Empirics41 suggest that inclusion of education rights in the Constitution does not affect quality and educational outcomes. The quality of education depends on socioeconomic, structural and policy variables such as expenditure per student, the teacher-pupil ratio, and family background.

Poor public service delivery and the tendency of the state to abdicate even essential services like education and health to the private sector has also contributed to inequality in Pakistan.

Free education and healthcare services are strong weapons against inequality. According to a report of Oxfam, these public services reduce the impact of skewed income distribution and put ‘virtual incomes’ in the pockets of the poorest of the poor in the society. Estimates suggest that for the poorest 20 % of families in Pakistan, sending all children to private low-free schools would cost approximately 127 % of their household incomes. Quality of such services is also crucial to make them reduce economic inequality and mitigate the effects of unfair income distribution. For example, if the public schools lag behind the privately-run schools in quality, children with low quality education would be unable to compete in the labour market. And in this way public services even if free would fail to make their desired impact on inequality and poverty alleviation.

(e) Regional Disparities and urban biased policies

The fifth broad source of inequality in our case are regional disparities. There exist huge inequalities between various geographical units. Some work on inequality in Pakistan even suggests that inequalities between districts are higher than within districts. The ruling elite have preferred certain regions over the others and this tendency of regional favoritism is still continuing. For example, there exists a clear rural-urban divide as far as development and fund allocation priorities are concerned.

Empirics on regional favoritism suggest that sound political institutions and good education can constrain regional favoritism of the political leaders. If we are really serious about tackling rising inequality and poverty, then all development projects should undergo a rigorous cost-benefit analysis. Findings42 of a study suggest that investment in social infrastructure are highly concentrated in the larger cities and urban areas in Pakistan, and the human capital infrastructure gap is fast increasing over time between the most and the least developed districts.

How to address inequality?

(a) Addressing inequality-the high road

Awareness about inequality and its detrimental effects on growth, development, and institution building is fast rising but a difficult part of the problem is the identification of appropriate policies and initiatives for improving income distribution within society in an efficient and cost-effective manner. The appropriate response for tackling inequality certainly depends on what caused it. In case of Pakistan, inequitable distribution of productive assets, rent-seeking, limited opportunities of mobility, and a regressive system of taxation are some of the factors behind extreme inequalities. If we want to adopt a high road for tackling extreme inequality, then the following measures are some of the options:

- Redistribution of land through effective land reforms with a ceiling per household (say 25 acres); identification of unproductive state land and its redistribution among the landless.

- Introduction of death duty– property and wealth beyond a certain reasonable limit left by a deceased person should be taxed heavily.Doing so will discourage investments in bricks and mortars which often turn into dead capital in developing countries. This step will increase spending and aggregate demand. Resultantly, economic growth will accelerate.

- Minimizing opportunities of corruption and rent-seeking; identification of the corrupt and rent-seekers and taking back the proceeds of corruption/ rents from them for investment of the same in sectors like education and public healthcare.

- Bringing back the proceeds of crime siphoned off to tax havens in Dubai and Switzerland; investing such proceeds for the amelioration of poverty, and making money laundering and corruption crimes punishable with capital sentence.

- Introduction of a welfare system as is prevalent in Scandinavian countries where the taxation system is such that it takes a major chunk of the income from the earners but in return provides free education, quality public health care and complete social security. It will fundamentally alter the priorities of how we collect taxes and where we spend them.

- Heavy taxation to discourage palatial houses and big cars etc; Encouraging small houses, say maximum of 10 Marla. All palatial buildings and residences (like Governor Houses and GORs) owned by the government to be sold in the open market and utilization of the proceeds for public welfare.

- Establishment of a permanent commission on inequality with the mandate to (a) propose measures for reducing inequality without compromising efficiency (b) monitor changes in inequality in the country

- Amendment in the Constitution that at least 20 % of the GDP will be spent on inequality-reducing projects like public education, healthcare, transfer payments social development, etc.

(b) Addressing inequality-the low road

The high road initiatives and policies require revolutionary changes which may not be forthcoming given the current socio-economic and political arrangements of society. The elite capture of politics and institutions is so entrenched that they will not let the power slip from their hands. On the other hand, the poor may not articulate their demands and achieve them due to what economists call ‘collective action problem’.

However, we should not forget the fact that a system which enriches the tiny elite and impoverishes the majority cannot continue for long. Complaining about inequality is a first step towards change of such a system. There may, however, be policies (the low road) which can be ‘win-win policies’ for the rich as well as the poor like universal primary education and universal healthcare because investing in people enhances the quality and productivity of the labour force. Similarly, raising the incomes of the poor increases domestic demand, and in turn encourages growth. Some policy measures and initiatives for reducing inequality can be as follows:

- Substantial increase in social spending– in order to reduce intergenerational poverty and inequality, it needs to be ensured that the poor children have access to reasonably good education. Cash/ income may be transferred to the poor families on the condition that their children attend school, eat properly, and meet other criteria to improve their wellbeing. Latin American countries which were considered the most unequal societies till 2000 are a case in point. After 2002 almost all the countries have witnessed an appreciable decline in income inequality. The most outstanding reason for decline in inequality in these countries is attributed to reduction in the skill premium due to redistribution of human capital among households, induced by rise in secondary school enrolment.43 Similarly, there is need to increase spending in public healthcare. In a nutshell, more intensive investment in human capital and equal access to high quality public services should be the target.

- Employment creation and promotion of SMEs. The constraints SMEs are faced with need to be removed. Financial institutions should be legally obligated to provide certain percentage of loans to SMEs and unemployed youth who are in search of starting some business. The collateral requirements can be relaxed in their case.

- Prioritizing public sector investments and encouraging establishment of industries in regions/ districts lagging behind the provincial average—more public sector development projects need to be directed to less developed districts and doing away with urban biased policies.

- Increasing tax-to-GDP ratio, expand tax base and make the taxation system more progressive. Emphasis should shift from indirect taxes to direct taxes. The rich and elite should not forget that their incomes are not a result of their own efforts only. They benefit from physical and social infrastructure for earning incomes. Policies are needed to reduce the potential for rent-seeking in society. Zero tolerance policy needs to be adopted for controlling corruption as it breeds inequality and poverty.

- As the poor do not have access to land and capital they have to therefore rely only on their labour to earn livelihood. The structural transformation in case of Pakistan is slow. Resultantly, the wage gap between the skilled and unskilled/semi-skilled labour is on a rise. So there is need to reduce this gap which can be done by upgrading the skills of the labour through vocational training and increasing minimum wages.

- A comprehensive policy on rural non-farm economy can be instrumental in reducing inequality and poverty in the rural areas of Pakistan. Neglect of the rural non-farm economy is one of the biggest factors responsible for inequality and poverty in rural areas. The socio-economic transformations that have taken place in the rural society in the last few decades also warrant a distinct treatment of a non-farm rural economy without confusing it with agricultural growth and productivity. The mechanization of agricultural farming that started in the wake of the Green Revolution has now started showing its full impact on rural employment. Sowing, harvesting, threshing, etc. is mostly done by the machines. Two profound changes in the rural landscape are now very much visible. First, agriculture is no more able to absorb the agriculture labour due to replacement of human tasks by machines and increasing population pressure. Second, the agriculturists no longer want to pay the agriculture labourers in kind which means that the price of labour (due to the phenomenon economists call stickiness of wages) has not kept pace with the price of agricultural commodities, having grave implications for food security. Added to this, our industrial sector failed to diversify itself. Consequently, it is unable to absorb the surplus agriculture labour.

Conclusion

Inequality is neither inevitable nor predetermined. It is a result of policies, preferences, choices and power interplay within a society and can be tackled by altering the political and economic power structures in society. The signals rising inequality is conveying need to be taken seriously. In our case the signals are that the system is conferring advantages on certain powerful groups and resultantly inequalities of income, assets, power, and influence are deepening. According to economists Hirschman and Rothschild, inequality in the development process is like a traffic jam in a tunnel. When one lane of traffic begins to move, it gives hope to those in other lanes that they will also soon move forward. But if only one lane continues to move and the others stay stalled, then the drivers in the stalled lanes become frustrated and engage in dangerous behaviour. Ours is a similar case. A tiny minority which has captured economic and political power is moving in the fast lane while the majority is stuck up in the traffic jam. If the common man loses hope in the system, a catastrophe is in the waiting even for the fast- lane- travelers i.e. rich and elite. We can choose between ‘the high road’ and ‘the low road’ policies but clinging to the status quo is no longer a choice.

References

- Ravi Kanbur, “Does Kuznets still matter?”, Working paper Charles H.Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management, Cornell University, January 2012

- Lewis, W.Arthur (1976), “Development and Distribution” in Employment, Income Distribution and Development strategy : problems of the developing countries ( Essays in honour of H.W.Singer) , edited by Alan Cairncross and Mohinder Puri; Holmes & Meir Publications, New York

- Alina Tuominen, “Reversal of the Kuznets Curve—study on the inequality-development relation using top income shares data”, WIDER Working Paper 2015/036 ( March,2015)

- Does Kuznets still matter? Ibid

- Edward L.Glaesar, “Inequality”, Faculty Research Working Paper Series, JFK School of Government, Harvard University, 2006

- Daron Acemoglu & James A. Robinson, “The Political Economy of the Kuznets Curve”, Review of Development Economics , 6(2), 183-203 (2002)

- Joseph E. Stiglitz , “The Price of Inequality”, Allen Lane ,an imprint of Penguin Books (page 85), 2012

- Michael W.Doyle & Joseph E. Stiglitz , “Eliminating Extreme Inequality: A sustainable Development Goal,2015-2030”, Ethics and International Affairs (March,2014)

- Johan P. Mackenbach, “Only the poor die young”, Project syndicate, June 17,2013

- Clare Bambara, “Why are the wealthier healthier?”, Project Syndicate, June 19,2013

- Melissa S. Kearney & Phillip B. Levine, “Income Inequality, social mobility, and the decision to drop out of high school”, http;//www.voxeu.org (May 28,2015)

- Jonathan David Ostry, Andrew Berg, Charalambos G. Tsangarides, “Redistribution, Inequality and Growth”, IMF Staff Discussion Note, February,2014

- Edward Glaesar, Jose Scheinkman & Andrei Shleifer, “The injustice of inequality”, 2002

- The Price of Inequality ibid ( page 191)

- Martin Rama, Tara Beteille, Yue Li, Pradeep K.Mitra & John Lincoln Newman, “Addressing Inequality in south Asia”, World Bank Group, 2015

- Oxfam Briefing Note , “Asia at the Crossroads-Why the region must address inequality now”, (January 20,2015)

- Richard H. McAdams, “Economic costs of inequality”, The Law School, University of Chicago, Nov,2007

- Oxfam International’s report “Even it up —Time to end extreme inequality” (October,2014)

- Jurgen K. Zattler , “The Debate on growing inequality – Implications for Developing Countries and International cooperation”, Courant Research Centre, Goettingen, Germany, March ,2015

- Kemal Dervis, “The Inequality trap” , Project Syndicate , March 8,2012

- Eric M. Uslander, “Corruption and Inequality”, Research Paper No.2006/34, UNU-WIDER , April, 2006

- Robert Skidelsky , “ Happiness, Equality , and the search for economic growth”, Guardian, October 22,2012

- End it now , Oxfam International ibid

- Roy Van der Weide & Branko Milanovic, “Inequality is bad for the growth of the poor ( But not for that of the rich), Policy Research Working Paper (WPS 6963), World Bank, July 2014

- Eliminating Extreme Inequality: A sustainable Development Goal,2015-2030 ibid

- Alex Cobham & Andy Sumner, “Putting the Gini back in the bottle? The ‘Palma’ as a policy relevant measure of inequality”, March 15, 2013

- Gabriel Palma, “Homogenous middles vs.heterogenous tails, and the end of Inverted U” ,2011

- Alex Cobham & Andy Sumner ibid

- Alice Krozer , “The Inequality we want— How much is too much?”, WIDER Working paper 2015/015 ( January, 2015)

- Abid S. Burki, Rashid Memon & Khalid Mir, “Multiple inequalities and policies to mitigate inequality traps in Pakistan”, Oxfam Research Report ( March,2015)

- Miles Corak, “Income Inequality, Equality of opportunity, and Intergenerational Mobility “, Journal of Economic Perspectives , volume 27,Number 3 (Summer 2013)

- Tilat Anwar, “Long-term changes in income distribution in Pakistan: Evidence based on consistent series of estimates “, Centre of Research on Poverty Reduction and Income Distribution ,2005, Islamabad

- Abid S. Burki et al ibid

- Haroon Jamal , “Growth and Income Inequality effects on Poverty: The case of Pakistan”, Social Policy and Development Centre ( SDPC), Research Report No 94, January,2015

- Jamil Nasir, “IMF Programs in Pakistan 1988-2008: An analysis” , Criterion Quarterly, Volume 6 Number 4 ,October-December,2011

- Thomas Piketty, “Capital in the Twenty –First Century”

- Jean-Marie Baland & James A. Robinson, “Land and Power: Theory and evidence from Chile”, American Economic Review, 2008

- John McDermott, “The future of inequality”, Financial Times, Oct 11, 2013

- David R. Henderson , “Rent seeking”, Library of Economics and Liberty

- Kevin M. Murphy, Andrei Shleifer & Robert W. Vishny, “Why is rent-seeking so costly to growth” AEA Papers and Proceedings, Vol.83 No.2, May, 1993

- Sebastian Edwards & Alvaro Garcia Marin, “Constitutional Rights and Education: An International Comparative Study”, NBER Working Paper No .20475, September,2014

- Abid A. Burki , “Exploring the links between inequality, Polarization and poverty: Empirical evidence from Pakistan, SANEI Working paper series, South Asia Network for Economic Research Institutes, Dhaka, 2011

- Giovanni Andrea Cornia, “Income inequality in Latin America—Recent decline and prospects for its further decline”, WIDER Working Paper 2015/020, February, 2015

The author is a graduate from Columbia University. Email: [email protected]