By

Stephen F. Browne*

Abstract

Within the UN, the development system comprises of a large and com- plex array of organizations and agencies, many of which are indepen- dently governed and financed. About 20 percent of the total UN develop- ment budget is spent in Asia, through almost 300 separate regional and country offices. UN assistance is of broadly three kinds: setting norms and stan- dards; promoting inter-country cooperation; and technical assistance. The last and most important is “hegemonic”, being mainly pre-funded “extra-budgetarily” by a limited number of rich country donors and reflecting their priorities.

The impact of the first type of assistance is broadly neutral. For the second, the UN’s role in regional cooperation has been muted, partly because of the limited impact of the UN’s regional commission. The third type, technical assistance, has had mixed results. It has been suc- cessful where it has been initiated by a programme country committed to development results. It has had a more limited impact where country ownership is weak.

Today, the region’s interest in, and involvement with, the UN devel- opment system is much diminished. One major reason is the highly suc- cessful development record of many Asian countries, particularly in the eastern part of the region, several of which have become major aid do- nors. Another is the existence of many alternative sources of assistance and support.To remain relevant, the UN development system needs to reform by consolidating around more uniform, distinctive and coherent objectives.

In the future, the strength of interest and engagement in the UN will depend to a large extent on the roles which the new powers in the region

- I. The UN development system

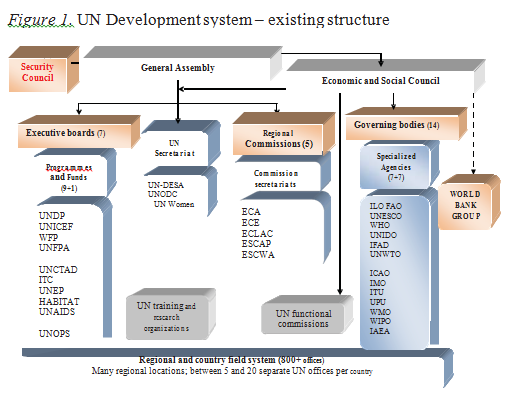

Development is one of the four principal pillars of the UN, along with peacekeeping, human rights and law, and humanitarian response. It accounts for about 60 percent of total annual UN spending (over US$ 13 billion), and employs the majority of the full-time staff. The “system”which engages inUN development activities in developing and transition-economy countries includes more than 30 funds, programmes, organizations, offices and agencies. Supporting the system, there are also several functional commissions and research and training organizations. (The World Bank Group is also a “UN specialized agency” but is outside the common staff administration, is independently governed, and not normally counted as part of the UN development system.)

As figure 1 makes clear, the UN development system (UNDS) is complex in structure. One reason is that itwas never conceived holistically, and has grown by accretion over a period of almost 150 years. When the United Nations was founded in 1945, some pre-existing international technical institutions were, in the words of the Charter “brought into relationship with the UN” as specialized agencies. Two of these organizations dated from the 19th Century.The International Telecommunication (formerly Telegraph) Union (ITU) and Universal Postal Union (UPU) were founded in Switzerland in 1865 and 1874 respectively. The International Labour Organization was more recent but dated from 1919 (Murphy 1994).Since 1945, many other agencies and organizations have been created under UN auspices, either as “specialized agencies” or as parts of the UN organization itself, under the authority of the Secretary-General and the General Assembly. The recent additions to the system have been the World Tourism Organization in 2003 (originally founded under a different name In 1946) which joined as a specialized agency, and UN Women, created within the UN secretariat in 2010.

Figure 1. UN Development system – existing structure

Regional and country field system (800+ offices)

Many regional locations; between 5 and 20 separate UN offices per country

The system is not only disparate in pedigree, but also in location, governance and mandate. The seats of the different entities are in 15 different countries. There are also more than 1,000 representative offices of the UNDS world-wide (and over 1,400 for the UN as a whole). All entities of the system report to the UN’s Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). However, because the 14 specialized agencies have their own memberships and governance systems, ECOSOC exercises a very limited writ. As discussed below, the atomized nature of the UN development system has limited its impact.

II. Three types of organization: three types of “UN aid”

Different parts of the system also provide different kinds of service. These are listed in the overview table (Table 1). In sum, the large “development pillar” of the UN comprises many widely dispersed and independently governed entities and a range of functions.

Table 1. Overview of UN Development System

| Agency/ Organisa- tion | Techni- cal stan- dards & norms | R e – search, data, infor- mation | Intergov- ernmental coopera- tion,policy, con- ventions | Technical assis- tance | Staff* | Ann. expend. ($mn.2008 or latest year) |

| UN SECRETARIAT | ||||||

| DESA | √√ | √ | √ | 509 | 69 | |

| UNODC | √√ | √ | √ | 467 | 231 | |

| UN Women | √√ | √ | 455 | 500 | ||

| FUNDS AND PROGRAMMES | ||||||

| UNDP | √ | √√ | 5,402 | 4,270 | ||

| UNICEF | √√ | √ | √√ | √√ | 6,430 | 2,808 |

| WFP | √ | √√ | 9,139 | 3,536 | ||

| UNFPA | √ | √ | √√ | 1,719 | 436 | |

| UNCTAD | √√ | √ | √ | 500 | 35 | |

| ITC | √√ | 290 | 49 | |||

| UNEP | √√ | √ | √√ | √√ | 994 | 131 |

| UN-HABI- TAT | √ | √ | √√ | 341 | 125 | |

| UNAIDS | √√ | 400 | 142 | |||

| REGIONAL COMMISSIONS | ||||||

| ECA | √ | √√ | √ | 644 | 59 | |

| ECE | √ | √√ | √ | 171 | ||

| ECLAC | √ | √√ | √ | 460 | ||

| ESCAP | √ | √√ | √ | 522 | ||

| ESCWA | √ | √√ | √ | 330 | ||

| SPECIALIZED AGENCIES | |||||||

| ILO | √√ | √√ | √ | √ | 2,500 | 424 | |

| FAO | √√ | √ | √ | √√ | 3,600 | 691 | |

| UNESCO | √ | √ | √ | √√ | 2,160 | 347 | |

| WHO | √√ | √ | √√ | √√ | 8,000 | 1,691 | |

| UNIDO | √ | √ | √ | √√ | 650 | 231 | |

| IFAD | √ | √ √ | 436 | 450 | |||

| UNWTO | √ | √ | √ | 90 | 379 | ||

| ICAO | √√ | √ | √ | √ | 700 | ||

| IMO | √√ | √ | √ | √ | 300 | ||

| ITU | √√ | √ | √ | √ | 822 | ||

| UPU | √√ | √ | √ | √ | 230 | ||

| WMO | √√ | √ | √ | √ | 300 | ||

| WIPO | √√ | √ | √ | √ | 939 | ||

| IAEA | √√ | √ | √ | √ | 2,200 | ||

| TOTALS | 51,700 | 16,604** | |||||

Source: FUNDS project

√√ primary function

√ secondary function

* excluding short-term and project staff

** includes humanitarian and emergency assistance of approximately $3 billion

UN assistance can be categorized into three types, distinguished by degrees of political and policy enagagement of participating states, and by the inherent organizational coherence (or incoherence) of the UN development system. The first and most straightforward is the “technical standards” function (in which research and information activities are included). States find a common purpose in international cooperation in order to resolve problems caused by interdependent relationships. Inter- state communications began at the ITU and the UPU in the nineteenth century because of the imperative to apportion international wave-bands and to allow mail to travel across borders. These two UN specialized agencies, along with five others created subsequently – IAEA, ICAO, responding to specific and universal technical needs.They establish common technical standards which are fundamental to international collaboration. Some other parts of the system are also “functional” in the Mitrany sense (1966) insofar as they help develop universal standards: WHO for health (and with FAO, for food safety3) and ILO for the work- place.

The second, more idealist, type derives from the need for cooperation through international organizations wherever there are shared perceptions of a problem and a readiness to develop a consensus around values and norms embodied by such organizations. The cognitive basis of such organizations are societal as well as state-based, and epistemic communities – including international networks – of non-governmental interests and advocacy groups are important. This “cognitive condition” (Rittberger and Zangl 2006)is the basis of inter-state cooperation through the UN and the closest approximation to global governance in such critical areas as environmental management (UNEP), regional cooperation (the UN regional commissions), health epidemics (WHO) and drug control (UNODC). In order to advance and safeguard progress in critical developmental areas, international cooperation leads to key global conventions, such as those in the environmental domain –the Montreal and Kyoto Protocols and the Stockholm Convention (UNEP)

– and in the social domain: the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (UN Women) and the most widely-ratified agreement of all, the Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNICEF). The various human rights conventions are also part of these idealist functions of UN cooperation. As ongoing negotiations on climate change illustrate, however, the development of new universal global regimes, is a hazardous process in which achieving coherence involves the deep political engagement of member states.

The third type is by far the most widespread, but also the most controversial, and is associated with the “neo-realist” school of organizational theory which recognizes that states have widely differing powers and influence (Mearsheimer 2001, Keohane 1984). Neo-realism is identified with a “hegemony condition” (Rittberger and Zangl 2006) but maintains that coercion and cooperation can be symbiotic. Hegemony has been the prevailing condition in UN technical assistance whereby first the United States, and then other rich country donors provided a substantial proportion of the resources and expected to be able to guide the behaviours of the institutions which they supported. This type of assistance is characterized by a high degree of incoherence.

III.

Type three: UN aid as donor patronage

The hegemonic nature of the most common form of UN aid, in terms of resources and visibility, means that it has come to resemble bilateral assistance, and thus a form of rich country patronage, rather contrary to the multilateral spirit of the United Nations. But was this orientation inevitable? To examine this question, it is necessary to look more closely into the origins.

Asia was the region in which multilateral technical assistance began. Under the League of Nations there were cautious provisions for countries to seek assistance, and a request for health advisors was received from the Republic of China (Nashat 1978).Given the delicacies of the political situation at the time in the region – with the Sino-Japanese conflict breaking out in 1931– and because of Chinese concerns over sovereignty, acceding to the request took time to negotiate. Experts were sent on the strict understanding that their role was to advise rather than decide. In 1933, the first resident technical adviser was installed

– a forerunner of the UN country representatives. By 1941, some 30 advisers had been fielded (Rist 1997).3

The example is important, not just because of the historical precedent for multilateralism, but also because it could have set a pattern for all the UN TA which was to follow in the post-war era. China and the League were at pains to ensure that the requesting government paid for everything, including the costs of the resident representative of the League. Paying for services was the pattern. Before the second world war, there were many other examples of countries requesting and purchasing specialized expertise from abroad. Technical assistance (TA) was essentially part of a bilateral commercial transaction (Morgan 2002).

Underlying the process of bringing new institutions and programmes to life there was alternation between two approaches to the relationships between developed and “under-developed” countries: the minority view was based on a philosophy of aid as a form of free patronage, but the other was based on a more equitable principle of partnership, which considered that – as in China before the war – requesting countries were more likely to receive pertinent advice and support if there was a financial obligation involved. In the late 1950s, an “operational and executive personnel” (OPEX) programme of UN TA was devised. OPEX personnel were not experts in the usual sense. They were provided through the UN, but recruited into public service by requesting countries which paid them local salaries. These were topped up by the UN, but on a strictly time-limited basis since the foreign personnel were expected to identify and train their own replacements within a one or two-year period. By 1961, after a successful two years of operation and with many requests outstanding, the program was given more permanent status within the UN and grew steadily.

Another partnership scheme was called “Funds in Trust” or TA on a “payments basis” in alternative UN jargon. Under this scheme, developing countries could obtain additional services to those received under UN TA by paying the increments themselves in hard currency, for example to extend the services of a foreign expert or in other ways prolong the life of a project. By 1965, no fewer than 64 countries had purchased services from the UN through this means, seeming to belie any presumption that foreign advisory services were unaffordable.

Another significant démarche in fostering partnership was the signing by requesting countries of “standard basic assistance agreements” (SBAA). Governments were expected to agree to assume responsibility for a substantial part of the costs of technical services with which they were provided, at least that part which can be paid in their own currencies. In addition developing countries were expected to defray the costs of local personnel, and the transportation, communications and medical services of all programme staff. Countries were also to provide office accommodation to resident representatives, and make contributions To local allowances of experts, including all local taxes. Each government was also required to pay cash amounts for “local counterpart costs” and uphold the diplomatic privileges and immunities of international personnel. Over the period 1950-64, during which donor countries pledged $400 million for UN TA, hard currency contributions from developing countries amounted to $45 million. Much more significant, however, was an estimated $900 million in local costs borne by the beneficiaries.To enforce the agreements, the UN would refuse additional requests for assistance to countries in arrears (Nashat 1978).

Notwithstanding the idealistic aspirations of partnership and a degree of cost-sharing in UN TA, the multilateral system did not achieve financial self-sufficiency based on the payments of client countries and was ultimately dependent on the financial contributions of the United States. The US was instrumental in setting up the Expanded Programme of Technical Assistance (EPTA) in 1950 in the wake of President Truman’s exhortation and the UN’s Special Fund (for pre-investment activities) established in 1959. From 1950 until 1966 (when EPTA and the Special Fund were merged to become the UN Development Programme), the US contributed more than half of all the funds for UN TA (Murphy 2006, Browne 2011). With a heavy dependence on the United States as principal donor went a degree of control (the hegemonic condition). There was a succession of five US Administrators at the head of the UNDP from its creation until 1999 and the United States exerted influence by a careful monitoring of the pattern of disbursements of UNDP funds by Congress, and the periodic threat to withdraw part or all of its contribution. This influence extended to other parts of the UN. The US has provided the Executive Director of UNICEF throughout its existence – more than 60 years. And while there has never been an American at the head of UNFPA, the US withdrew its entire contribution between 2002 and 2009 because of Congress’s objections to the organization’s birth control policies. The US has also withdrawn from some of the UN specialized agencies, such as UNESCO in 1984 (rejoining in 2003), from ILO (1977-80) and from UNIDO (1996 to the present), citing variance with US policies.

Thus UN TA soon began to veer strongly towards patronage under the influence of the United States, and later, other rich country donors. As the aid industry multiplied in size, with major new bilateral programs leading the way, developing countries were presented with a wide array of essentially free technical assistance to supplement multilateral sources. Bilateral aid was almost invariably an adjunct of donor foreign policy and bought influence (Browne 2006). But aid from one source had to compete with other offers. In these competitive circumstances, it was inevitable that UN assistance should also come to resemble patronage. The financial obligations of the recipient countries were steadily phased out. Even the terms of some SBAAs were suspended.

The UN development system that emerged, then, was not only complex in composition, but a source of multiple forms of “free” services. Funding came predominantly from a limited number of developed countries, and the agencies and organizations of the system sought to disburse it effectively. Thus while purportedly meeting developing country needs, UN TA was supply-sided and UN agencies saw their accountability to their donors as at least as important as to client countries. It was the “golden rule” of aid: he who has the gold makes the rules. The first head of UN TA remarked on the resulting distortions early on: “it sometimes seemed that the chief reason for undertaking a particular project was not the fact that the applicant government had placed it high on its list of priorities, but merely that a particular agency had money available (from a donor) and was willing to finance it.” (Keenleyside 1966,164). Much later, little had changed. A recent comprehensive review of UN development assistance had this to say: “ambiguity about sovereignty has all along characterized the aid relationship, especially aid through the UN system. In actuality, the agencies that determined and implemented the aid have had a strong, even decisive, influence not only on who received the assistance but also on the purposes it served and the principles that governed its implementation”(emphasis added) (Stokke 2009, 485). Behind the agency “influence” is donor funding and the dominance of the donors in UN aid has, moreover, increased over time. A limited number of countries provide the bulk of the regular budget resources, which support permanent staff and administration. But in many UN agencies and organizations, the “non-core” (earmarked) contributions specifically for TA are now larger than the core. In the case of UNDP, non-core resources are four times greater. Non-core resources are not subject to scrutiny by governing bodies and are usually provided for specific purposes determined by each donor.

IV. The UN in Asia

The UN presence in Asia is extensive. There is a total of 299 separate country and regional offices of the UN, of which 222 representing UN development agencies and organizations (Table 2, on the next page). These numbers compare with 479 and 345 in Africa (smaller population, but more countries) but they are still high when compared with the financial scale of UN development assistance, especially when it is considered that there is almost no pooling of administrative support, with each office reporting primarily to a remote headquarters. The numbers (here and in other regions) are indicative of the steady proliferation of the UN development system without reference to any systematic construct and has allowed a significant amount of duplication and overlap of UN development activities within countries and regions.

Table 2. UNDS Country and Regional Offices in Asia-Pacific

| UN* | UNDP | UNI- CEF | UNFPA | WFP | WHO | FAO | UNES- CO | ILO | OtherUNDS | WB | OtherUN** | TOTALS | ||

| UNDS | UN*** | |||||||||||||

| Afghani- stan | x | x | X | x | x | x | x | x | x | 6 | x | 5 | 14 | 21 |

| Bangla- desh | x | X | x | x | x | x | x | x | 1 | x | 2 | 9 | 12 | |

| Bhutan | x | X | x | x | x | x | – | – | 6 | 6 | ||||

| Cambodia | x | X | x | x | x | x | x | x | 2 | x | 3 | 10 | 14 | |

| China | x | X | x | x | x | x | x | x | 3 | x | 2 | 11 | 14 | |

| EastTimor | x | x | X | x | x | x | x | x | x | 1 | x | 2 | 9 | 13 |

| Fiji | X | X | x | x | x | X | 3 | 1 | 9 | 10 | ||||

| India | x | X | x | x | X | x | x | X | 5 | x | 1 | 13 | 15 | |

| Indonesia | x | X | x | x | x | x | X | x | 3 | x | 5 | 11 | 17 | |

| Iran | x | X | x | x | x | x | x | 2 | 3 | 9 | 12 | |||

| Korea,DP | x | X | x | x | x | x | – | – | 6 | 6 | ||||

| Korea, R | x | x | x | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | |||||||

| Laos | x | X | x | x | x | x | 2 | x | 4 | 8 | 13 | |||

| Malaysia | x | X | x | x | 1 | 1 | 5 | 6 | ||||||||

| Maldives | x | X | x | x | – | – | 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| Mongolia | x | X | x | x | x | x | x | x | 1 | x | 2 | 9 | 12 | |||

| Myanmar | x | X | x | x | x | x | x | 2 | 1 | 9 | 10 | |||||

| Nepal | x | X | x | x | x | x | x | x | 1 | x | 4 | 9 | 14 | |||

| Pakistan | x | X | x | x | x | x | x | x | 3 | x | 5 | 11 | 17 | |||

| Papua NG | x | X | x | x | 1 | x | 2 | 5 | 8 | |||||||

| Philip- pines | x | X | x | X | x | x | x | 3 | x | 4 | 10 | 15 | ||||

| Samoa | X | X | x | x | x | x | x | – | – | 7 | 7 | |||||

| Sri Lanka | x | X | x | x | x | x | x | x | – | x | 2 | 8 | 11 | |||

| Thailand | x | X | X | X | x | x | X | X | X | 9 | x | 4 | 17 | 23 | ||

| Vietnam | x | X | x | x | x | x | x | 3 | x | 2 | 10 | 13 | ||||

| Totals | 4 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 17 | 25 | 21 | 16 | 17 | 53 | 16 | 57 | 222 | 299 | ||

Sources: FUNDS project and United Nations 2010.

X = regional office x = country office

* denotes peace-keeping mission, regional commission

** includes humanitarian agencies (UNHCR, OCHA etc), UNIC, UNOHCHR and IMF

*** Total UN includes IMF and World Bank

Among the 10 largest UN programmes within countries, Asia accounted for two in 2008 (Table 3). Afghanistan is by far the largest, but the figure includes a substantial proportion of reconstruction and humanitarian aid. The table also reveals a wide variation in the amounts of UN assistance per capita. In terms of financial value, by far the largest components of these programmes are in the form of technical assistance.

Table 3. Top 10 programme countries of UN development system, 2008

| Rank | Recipient | Development-related expenditures [DEV] (mn US$) | DEV as % ofGNI (%) | DEV expenditu- res per capita (US$) |

| 1 | Sudan (L) | 1,220 | 2.7 | 29.5 |

| 2 | Afghanistan (L) | 842 | 7.9 | 29.0 |

| 3 | Palestine OT | 586 | — | 148.9 |

| 4 | DR Congo (L) | 562 | 5.7 | 8.8 |

| 5 | Ethiopia (L) | 539 | 2.4 | 6.7 |

| 6 | Somalia (L) | 373 | — | 41.8 |

| 7 | Kenya | 339 | 1.2 | 8.8 |

| 8 | Bangladesh (L) | 302 | 0.4 | 1.9 |

| 9 | Iraq | 275 | — | 9.0 |

| 10 | Uganda (L) | 273 | 2.0 | 8.6 |

L = Least developed country

Sources: United Nations 2010; FUNDS project

In a short paper, it would not be feasible to provide a comprehensive review of UN development aid in Asia in all its three principal forms. The purpose, rather, is to provide illustrations of the nature and impact of the UN development system in order to help determine the significance of the UN DS to Asian development, in the past and in the future.

1. Standards and information.

Most Asian countries are members of the standard-setting agencies and conform to their technical norms. (Thesevenstandards agencies also provide technical assistance, but mainly in support of their functional roles.) The UN role in standard-setting has remained static over many years. New areas of importance to the region, such as internet governance and regulation, are being managed by non-UN organizations (such as the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, ICANN) and the field of management and quality standards is shared with organizations such as the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) which has been described as “the largest non-governmental global regulatory network” (Murphy 2009). These organizations are differently constituted and comprehensively involve non-governmental interests.

Also included in this type of assistance is the work of research and information which many organizations of the system engage in. In sum, the purely functional role of the UN is long-established and has remained a relatively minor part of UN development in Asia.

2. Cooperation.

The second (“cognitive”) area of UN development activity involves cooperation across borders in specific areas of concern. Here, while the UN’s global role has been significant – especially in the domain of environmental management – its regional impact has been quite limited. This is partly because of the very muted success of the UN’s Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, based in Bangkok.

From the founding years of the UN, the role of the regional commissions was poorly defined. Indeed, “there was nothing inevitable about their establishment in the mid-1940s. Regional commissions were not viewed as a necessary part of the UN vision” (de Silva 2004, 140). The first one to be established was the Economic Commission for Europe (ECE) in 1947, and it became a centre for research on reconstruction and development in the region. A second function could have been the coordination of assistance to European countries, but when the Marshall

Plan was established in 1948, a separate Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC, forerunner of today’s OECD) was established, thus effectively ending any prospect of the ECE becoming a significant development centre (Toye and Toye 2004). The ECE and the Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLA) established in 1948 nevertheless succeeded in recruiting some of the brightest and most original development economists of their day to their research functions.

ESCAP (originally, the Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East, ECAFE), which was established in 1949 as part of an inexorable political process of creating a commission for each major region, did not attract the same calibre of professional staff, either at its inception or later and never became a significant centre of research. The regional concept itself was challenging. Asia at the time was war-torn and turbulent and the region (later to be bracketed with the Pacific) was so large and diverse that it scarcely constituted a region with anything like the same unity of cultural identity as Latin American. The region is still the most conflict ridden, with many chronic ongoing disputes between neighbours.

Notwithstanding the ECE experience, the UN anticipated that ECAFE could become a mechanism to coordinate reconstruction. But despite the fact that six out of ten of the original members were industrialized countries outside the region, reconstruction aid was not forthcoming. As the membership expanded to include a large majority of now-independent developing countries from the region, apotentially important vocation for ECAFE nevertheless beckoned, and that was the promotion of sub-regional cooperation based on infrastructure and trade. ECAFE’s early initiatives included the Asian Highway and the Trans-Asian Railway projects, but while tentative plans were laid, they never materialized as conceived, for several reasons. Intergovernmental relations within the region were complex and some countries – like Burma – were reluctant to open their borders to neighbours. These projects would also have required substantial capital investments which were not forthcoming. Another reason for failure was that the ECAFE secretariat did not sustain its commitment to these projects, which might have helped to ensure partial implementation.

There was partial success with two other initiatives begun in the 1970s: the Bangkok Agreement for trade and the Asian Clearing Union (ACU). The former was a programme of selective tariff reduction among a few non-contiguous countries of the region and it had a limited impact on trade expansion. The ACU, based in Tehran, had a small membership of national central banks and has operated over many years; however, the size of transactions between countries has been restricted by the exclusion of major traded commodities like petroleum. Another promising initiative was the proposed Asian reserve bank, whose author was Robert Triffin, which could have been the forerunner of a regional “IMF”. But the plan never got off the ground. (However,when, following the Asian financial crisis of 1997-8, a proposal was mooted for a regional system of pooling reserves – the Chiang Mai Initiative of 2000 – ESCAP and the UN were not involved.)

Two successes which emerged from ECAFE/ESCAP’s intergovernmental forums were the creation of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in 1966 and the Mekong Committee of four riparian countries (Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam). The Mekong Committee – which was managed and funded by the UN Development Programme (UNDP),becoming independent in 1995 – has been perhaps the most successful of all the UN-sponsored regional initiatives in Asia. It has provideda centre of research and a fulcrum of arbitration among the member countries in the administration of the region’s largest river delta.4

The ADB has also grown into a highly successful regional institution, becoming wholly independent of its UN origins at an early stage. Its subsequent success eclipsed the role of ESCAP as a centre of research and information and is much closer to the original UN concept of a regional development financing organization. In fact the child out-grew the parent. Ithas been described as “a serious rival and competitor” to ESCAP (de Silva 2004, 139).

ESCAP, with funding from UNDP, also created a number of othe regional institutions. The Asian Institute for Economic Development and Planning (AIEDP) was created in 1964, and in 1970 the Asian Centre for Development Administration (ACDA). The two were merged in the 1980s to form the Asia-Pacific Development Centre (APDC) which moved from Bangkok to Kuala Lumpur where it has remained. These organizations never fulfilled their intended roles as major development research centres for the region.

Several other regional institutions were established in the 1960s and 1970s, when the UN was active in trying to bolster the fortunes of traded commodities. These included the Asian Coconut Community, the Association of Natural Rubber Producing Countries, the Pepper Community and the Centre for Grains, Pulses, Roots and Tubers. Because these commodities were not exclusively regional, some of these organizations (e.g. the Pepper Community) were superseded by global equivalents.

Besides ESCAP, other UN development organizations have also actively promoted regional cooperation, through multi-country programmes or regional institutions. There is no doubt that these initiatives, in bringing together government policy-makers of the region to discuss common concerns within their respective sectors and domains, have facilitated exchanges of experience. However, the specific nature of the problems confronting individual countries, and the necessary involvement of non-governmental and private actors in development, have limited the capacity of these initiatives to craft solutions.

A fundamental weakness of regional cooperative arrangements in the region – whether or not with the sponsorship of the UN – has been inadequate resources. Many regional programmes and institutions have come and gone, and those that have been sustained on a long-term basis have usually had to rely on preponderant support from the host country (e.g. Malaysia for the APDC, India for the Asia and Pacific Centre for the Transfer of Technology, South Korea for the Asian and Pacific Training Centre for Information and Communication Technology for development, and Japan for the Statistical Institute for Asia and the Pacific). In any circumstances, regional cooperation can be a hard sell, because of the lower priority given to out-of-border as compared to domestic concerns. Also, some initiatives outlived their usefulness and were destined to be time-limited. However, too many initiatives began as proposals originally emanating from the secretariats of UN entities and were started before a robust business plan and sustainability programme had been developed.

Meanwhile, the two best examples of comprehensive inter- governmental regional cooperation – the 10-member Association of South-east Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the 21-member Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) – have emerged with virtually no support from the UN system. In the early days of ASEAN, the UN undertook a comprehensive study of industrial and trade complementarity among the original six members, which gave impetus to the integration process. Since then, however, ESCAP and the UN played very littlepart in the development of ASEAN, and ESCAP is not an invited observer in either grouping.

3. Technical assistance.

To some extent, UN sponsorship of regional programmes has featured the “hegemonic” condition insofar as individual donor countries have sought to use UN organizations as conduits for their patronage. The newer donors are no exception. For example, now that South Korea has become a major donor to ESCAP, it hosts a new ESCAP subregional office for East and Northeast Asia, and has initiated and promoted a regional “green growth” strategy which reflects what the Government describes as its “number one priority in every sector of policy formulation”.5China and India also each host, and substantially support, ESCAP regional institutions in their capital cities. These programmes and institutions are mechanisms of influence within the region for their sponsors.

Most UN development assistance to the region, however, takes the form of country-based technical assistance where donor patronage is most pronounced, for the reasons which were outlined above. With some thirty UN development entities active within the region, the majority with some form of permanent representation through country or regional offices, for the most part operating independently, there is a substantial number of TA projects ongoing at any one time. In 2008, the value of TA spending by the UN development system in the region was estimated to be $US2.7 billion, which is about 20 percent of global spending (United Nations 2010). Given the scale of activities, it would be impossible to provide even an overview of the impact of so many separate initiatives, of which a small, but illustrative sample is shown in Table 4. However, what can be attempted, with reference to a few examples, are some parameters of success and failure of UN TA in the region.

Table 4. Selected examples of UN Development System activities in Asia

| Agency/ Organization | Technical services | |||

| Technical standards & norms | Research, data, infor- mation | Intergovernmen- tal cooperation, policy, conven- tions | Technical assistance | |

| DESA | Public adminsitration support | |||

| UNODC | Narcotics production | Crop substitution | ||

| UNDP | Regional, na- tional human devt. reports | Mekong RiverCommission | Electoral assistance | |

| UNICEF | National child assessments | Water and sanitation projects | ||

| WFP | Food for work schemes | |||

| UNFPA | Access to reproduc- tive health | |||

| UNCTAD | Generalized system of trade prefer- ences | ASYCUDA: au- tomated customs administration | ||

| Agency/ Organization | Technical services | |||

| Technical standards & norms | Research, data, infor- mation | Intergovernmen- tal cooperation, policy, conven- tions | Technical assistance | |

| ITC | Organic export pro- motion | |||

| UNEP | Montreal Protocol Kyoto Pro- tocol Stockholm Convention | |||

| UN-HABI- TAT | Urban water supply | |||

| UNAIDS | Regional statistics | Support to nationalAIDS Commissions | ||

| ESCAP | Annual sur- veyRegional

statistics |

Regional institu- tions | ||

| ILO | Labour stan- dards | Migration policy | ||

| FAO | Codex Ali- mentarius | |||

| UNESCO | World Heri- tage sites | Anghkor Wat, Borobudur restora- tion | ||

| WHO | Avian flu, SARScontainment | |||

| UNIDO | Support to MontrealProtocol compliance | |||

| IFAD | Sustainable rural development | |||

| UNWTO | Regional tourism sta- tistics | |||

| Agency/ Organization | Technical services | |||

| Technical standards & norms | Research, data, infor- mation | Intergovernmen- tal cooperation, policy, conven- tions | Technical assistance | |

| ICAO | Technical standards | |||

| IMO | ||||

| ITU | Asia-Pacific Institute for Broadcasting Development | Rural ICT pro- gramme | ||

| UPU | ||||

| WMO | ||||

| WIPO | ||||

| IAEA | ||||

The first example is Singapore. Now a successful industrialized economy and long since independent of UN assistance, the country owed its early development progress in part to the UN. In 1960, Singapore approached EPTA for assistance with industrial planning and received two missions which were instrumental in laying the foundations for its manufacturing development. As a measure of the value attached to this technical advice, the Government continued to invite the Dutch mission leader (Albert Winsemius) back and he remained “one of its main economic architects for the next 25 years” (Murphy 2006, 101). For many years, the UN was the principal source of TA in Singapore. A second related example is from China. In 1979, at the beginning of the country’s turn towards market reform, China requested UNDP to open a country office in Beijing. One of the earliest projects was the organization of a study tour for the vice-minister of foreign trade to visit export-processing zones on four continents. That project helped to spark the creation of the special economic zones in Guangdong province which have been one of the engines of subsequent Chinese development. Twenty years later, that vice-minister (Jiang Zemin) had become the country’s president and acknowledged his debt to the UN.

UN TA initiatives like these are far from unique. Indeed, missions to Asian countries to advise on the development of industry and foreign trade have been repeated in virtually every country. What made the Singapore and China examples successful was the fact that the request for assistance had been clearly initiated by the governments concerned (and not proposed or encouraged by the UN) and that the missions had been followed by a commitment to pursue a development course, utilizing the advice obtained.As with the early examples of UN TA which had used OPEX and funds-in-trust modalities, the cost was not a factor to the country concerned, only a desire to obtain the best technical advice. The other valued aspect of multilateralism illustrated by these examples was access to the kind of neutral and objective advice which would not have been forthcoming through bilateral aid.

Another rather different, and more recent, example comes from India. In 1990, UNDP produced the first global Human Development Report (HDR) which featured, as a new measure of development progress, a human development index based on income, education and longevity. Soon afterwards, UNDP began producing national HDRs in a growing number of countries, but India took a different approach. In 1995, the state of Madhya Pradesh began to produce its own annual reports and these state-wide HDRs soon began to grow in number within the country. Soon, India’s planning commission began to take these HDRs under its own wing and they have been used as regional barometers of development progress (Browne 2011).

The lesson to be drawn from this example is that the UN had become a source of original development thinking – and in this case the invention of a new paradigm – and that its real value could best be gauged by the willingness of countries to adopt and adapt it for themselves. As an echo of the “hegemonic” idiom, UNDP’s human development report office initially expressed its regret that in India it had lost quality control over the HDRs. But it ought instead to have been a source of satisfaction that a country with the intellectual wealth of India had wanted to take full advantage of the human development concept as an inspiration for policy-makers.

These examples point up the importance of country ownership of the development process, a simple concept which is vociferously – and somewhat ironically – touted by aid donors (for example through the Paris Declaration), but rarely allowed for because it is systematically undermined by traditional TA which, whether through bilateral or UN multilateral aid channels, reflects the hegemonic instincts of funders rather than the expressed interests of the demandeurs. Unfortunately, much UN TA in Asia (and other regions) follows this traditional pattern and helps to explain why projects typically last much longer than originally planned, and once completed, often have to be repeated in a similar guise years later.

There are other problems which undermine the effectiveness of UN assistance. The UN development system in every region is atomized into multiple country representations and is susceptible to duplication. Many UN entities are working in parallel on projects on water and sanitation, energy, micro-finance, technology transfer and investment promotion – just to mention a few of the areas where the overlaps are most frequent. In recent years, recognizing the wastefulness of the UN’s lack of coherence, the system has cautiously begun to promote common programmingwithin each country. In all countries there is now a single “UN development assistance framework” (UNDAF), and in two countries of the region – Pakistan and Vietnam – there is an experiment in “delivering as one” which is aimed at promoting a single UN office, programme, budget and representative. But these objectives are still distant as long as the different entities of the development system maintain the same degree of independent governance and funding.

Coherence of the UN system is nowhere more important than in countries undergoing major programmes of reconstruction, such as Afghanistan or Timor Leste. For relief and humanitarian assistance – which is not the primary concern of this paper – the UN has become more cohesive in recent years, under the auspices of the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). But longer-term recovery programmes, for which the UN is often best-placed to perform a leading role, continue to suffer from the inherent discombobulation of the development system. In Afghanistan, where the UN has its largest Asian development programme, the dissonance has been described by two people formerly working within the government (one as Finance Minister) as follows: “work is often carried out in silos and is therefore at cross-purposes…in the wake of a peace agreement, hundreds of people descend on the capital city from numerous agencies, each booking successive meetings on the same topics with the same people. This imposes a huge cost in time and results in multiple projects and plans with as many as fifty different “strategies” for the same country.” (Ghani and Lockhart 2008, 174-5).

V. Conclusions: the future of UN assistance in Asia

It is tempting to conclude that the overall impact of the UN development system – a large collectivity of UN agencies – has been limited, in Asia and in other regions.There are several reasons for this conclusion, which this paper has attempted to highlight.

First, the major part of UN development assistance became a conduit early on for patronage by the major OECD donors, and to that extent was not a distinctive alternative to bilateral programmes. Moreover, as discussed above, the reliance of most UN agencies on non-core (earmarked) funding for TA has increased, not decreased, since the turn of the millennium. Pre-funded assistance, whether multilateral or bilateral, tends to reflect the priorities of the funding sources and implementing agencies, rather than those of the programme countries.

Second, the UN development system is large, unwieldy and fractured. The totality of its grant assistance is significant as compared to other multilateral donors. But it emanates from some 30 separate organizations with their own sets of priorities and their own systems of governance and funding, and is susceptible to overlap. The programmes of each part of the system are mostly small in size and do not cohere around a distinctive UN identity.

Third, there is also an important sense in which the UN agencies continue to live in the past. In the early stages of post-war development, there was a consensus around the need for technical (as well as financing) solutions to the problems of the newly independent countries. The international organizations that grew up during that period, right into the 1960s, were technocratically-based, responding to development challenges with technical solutions. It was as if many different technical inputs could somehow be bolted together to provide a holistic development solution. It is clear from the nature of the development process, however, that contextual considerations – including especially the political and institutional – are of paramount importance (Bøås and McNeill 2003). Development is fundamentally a political process, and experience shows that enlightened leadership and sound policies count much more than starting conditions, geography and resource endowments as the key ingredients for development progress. There are many technical obstacles, but they cannot be overcome merely through the availability of technical solutions. In Asia in particular, where most countries have the capacity to meet their technical needs, the UN development system has for the most part failed to deliver credible policy expertise.

As a development partner in the traditional sense, the UN system is of declining relevance to the region. This is to be welcomed insofar as it is attributable to the rapid development progress achieved, particularly in East Asia. The UN played a small but significant role in some of these successes, where the partner countries were clearly the owners of the process. But these examples were among the exceptions.

To examine UN development effectiveness more closely, the Future of the UN Development System (FUNDS) project undertook a “global perceptions survey” of stakeholders in 2010 (FUNDS Project 2010). More than 3,200 responded to the questionnaire, the majority from private sector, NGO and academic backgrounds – reflective of the composition of the intended development beneficiaries of UN assistance.

One-third of the respondents were from Asia and the survey also solicited individual comments on the UN system. Tellingly, one Asian respondent stated that the UN “is not neutral — the funders control its agenda, overriding its principles of neutrality.” The survey also found that a large majority (80 percent from North and East Asia, 74 percent from South and West Asia) were in favour of fewer UN agencies and also supported a single UN representative in each country (81 percent in both sub-regions). Selected comments on the need for consolidation are as follows:.

Public perceptions of the UN development system in Asia: proliferation

“There are far too many individual UN agencies and organizations. Several could be merged (e.g. UNCTAD and UNIDO; or FAO and WFP). Some serve little purpose. Indeed, many could be rolled into some kind of “super UNDP”, thus reducing overhead costs, eliminating multiple parallel country programmes, offices and staff, and eliminating overlaps and gaps, freeing up more resources for implementation.”

“Some agencies are duplicating functions and are not really being felt in member nations as to their relevance of functions.”

“Too many organizations, but no budget to support the goals.”

“I am finding that linkages among UN organizations and agencies are weak in terms of uniform messages on global issues, or perhaps if not weak, not promptly systematic in terms of timing and frequency of action.”

Source: Global Perceptions Survey, Future of the UN Development System (FUNDS) Project, April 2010

A further concern revealed by the survey was that the UN system had not moved with the times and was no longer the best source of expertise or advice in several domains. These domains may be outside the purview of the UN agencies, or in areas where expertise has moved beyond the capacities of agency staff. The calibre of the staff themselves

– e.g in providing policy advice – was also perceived as a potential handicap by the FUNDS survey.

Public perceptions of the UN development system in Asia: staffing

“The quality of UN staff varies enormously with some excellent performers and many mediocre to blatant under-performers. But the management systems do not reveal such differences and weaknesses with many staff getting promoted despite weak performances. The UN has no competitors where it does what it was made for, but often ends up doing things that NGOs or the World Bank are better equipped for.”

“The UN selects the lowest qualified, youngest, most inexperienced staff of almost all agencies.”

The UN is top-heavy in terms of staff, and over-reliant on UN volunteers and interns to fill gaps at the technical level.

Source: Global Perceptions Survey, Future of the UN Development System (FUNDS) Project, April 2010

The survey suggests a number of areas in which the UN development system needs to reform to remain relevant. The most pressing is the achievement of greater coherence. A reform programme begun in 2007 as the result of an authoritative report by a high-level panel (co-chaired by the Prime Minister of Pakistan at the time) proposed a much closer alignment of UN agencies within each developing country (United Nations 2007). But consolidation of the UN development system will not suffice. Trying to bring about a convergence of so many disparate and parallel pre-funded activities will not enhance coherence but merely add to the complexities of programme management, as UN country offices are already finding. If there is a single authoritative head of the UN development system at country level, as a more distant objective, it should be someone with policy sophistication and specialized knowledge of local development needs, able to adjudicate the most appropriate UN response from amongst the agencies and organizations of the system.

Perhaps most important of all, however, would be a clearer sense of exactly what the UN system stands for in development, and what makes it distinctive from the other multilateral donors and regional development banks which are currently seen as alternative, and often superior, sources of assistance. The UN’s Millennium Development Goals of 2000 were a useful formulation of a possible UN agenda, but they do not clearly delineate roles for the UN to play, as distinct from other bigger donors. At an international conference in the UK in November 2010, participants proposed that the UN’s development efforts should converge around human development, human rights and human security. If these were to become the central themes, the major role of the UN and its agencies might be to work with member states to draw up international conventions and standards, monitor their compliance and assist countries to meet them.

But what the UN development system does, and becomes, will depend in part on the influence of Asian countries: in particular, the world’s two most populous developing countries, as well as South Korea. Since all three are now significant aid donors, their relationship with the UN development system has inexorably changed. India has been a vocal proponent of UN development cooperation from its inception, playing an important part in fashioning the roles and scope of some of the agencies (such as UNIDO and UNCTAD). With China, it has been a very active player within the Group of 77, the developing countries’ global negotiating bloc. But India today, with China and South Korea, are also interested in the UN development system more from an “eastern donor viewpoint”. In standard-setting, these countries have become much more actively involved since the mid-1990s, as “standards makers” in areas such as information technology. And as the emerging Asian countries grow in significance as technical innovators, their engagement in intellectual property protectionism (through WIPO) is increasing commensurately.

The major Asian powers are also beginning to play a more prominent role in global cooperation, in trade, climate change and other areas. Under UN auspices, these cooperative arrangements, and the universal conventions which underpin them, are likely to come under growing scrutiny and influence from Asian governments, which are less attuned to the western liberal traditions which have formed the basis of global governance arrangements hitherto. But invoking the hegemony principle, influence will be determined by financial stake. In 2010, the assessed contribution to the UN of the world’s second-largest economy was a mere 3.2 percent (as against 22 percent for the United States). For India and South Korea, it was 0.5 percent and 2.3 percent respectively.

Given the weakness and poor coherence of the UN’s institutions, Asian countries are unlikely to vest the UN with any roles of consequence in inter-state regional or sub-regional cooperation. The UN’s functions are likely to remain at the level of ad hoc cooperative programmes (e.g. in trafficking or migration) and innocuous declamations of regional positions in global negotiations.

Asia’s principal UN influence will be through TA. This paper has already referred to the “hegemonic” sponsorship by China, India and South Korea of regional institutions and programmes. These initiatives both at regional and country levels – are likely to increase in number with the Asian donors using individual agencies and organizations of the UN development system as conduits for their influence within the region. These non-core funding sources will help to boost the UN’s level of TA activity in Asia, but will add further to the challenges of coherence.

The alphabet soup

FUNDS AND PROGRAMMES Seat (founding year)

| UNDP | UN Development Programme | New York (1965) |

| UNICEF | UN Children’s Fund | New York (1946) |

| WFP | World Food Programme | Rome (1963) |

| UNFPA | UN Population Fund | New York (1969) |

| UNCTAD | UN Conference on Trade & Development | Geneva (1964) |

| ITC | International Trade Centre | Geneva (1964) |

| UNEP | UN Environment Programme | Nairobi (1972) |

| UN-HABITA | T Human Settlements | Nairobi (1978) |

| UNAIDS | UN Joint Programme on HIV and AIDS | Geneva (1996) |

| UNEGEEW | UN Women | New York (2011) |

UN SECRETARIAT

| UNDESA | UN Department of Economic & Social Affairs | New York (1945) |

| UNODC | UN Office of Drugs and Crime | Vienna (1997)* |

| UNOPS | UN Office of Project Services | Copenhagen (1973) |

REGIONAL COMMISSIONS

ECA Economic Commission for Africa Addis Ababa (1958) ECE Economic Commission for Europe Geneva (1947) ECLAC Economic Commission for Latin America and Caribbean Santiago

(1948)

| ESCAP | Economic Commission for Asia and Pacific | Bangkok (1949) |

| ESCWA | Economic Commission for W. Asia | Beirut (1973) |

SPECIALIZED AGENCIES

ILO International Labour Organization Geneva (1919) FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN Rome (1945) UNESCO UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Paris (1945) WHO World Health Organization Geneva (1948)* UNIDO UN Industrial Development Organization Vienna (1985)# IFAD International Fund for Agricultural Development Rome (1977) UNWTO UN World Tourism Organization Madrid (2003)*# ICAO International Civil Aviation Organization Montreal (1945) IMO International Maritime Organization London (1958)* ITU International Telecommunication Union Geneva (1865)* UPU Universal Postal Union Berne (1874) WMO World Meteorological Organization Geneva (1951) WIPO World Intellectual Property Organization Geneva (1970)* IAEA International Atomic Energy Agency Vienna (1957)

Training and research institutions Functional commissions

| UNITAR UNICRI | Training and ResearchCrime and Justice Research | Sustainable developmentNarcotic drugs |

| UNIDIR UNRISD UNU | Disarmament ResearchSocial Development

UN University |

Crime prevention Science and technology Status of womenPopulation and Development

Social Development Statistics |

# date of joining UN as specialized agency

* different name/status prior to UN

References

Alexander, Yonah. 1966. International Technical Assistance Experts: a Case Study of the UN Experience. New York: Praeger.

Bøås, Morten and Desmond McNeill. 2003. Multilateral Institutions: A Critical Introduction. London: Pluto Press.

Browne, Stephen. 2006. Aid and Influence: Do Donors Help or Hinder? London: Earthscan. Browne, Stephen. 2011. The UN Development Programme and System. London: Routledge (forthcoming)

De Silva, Leelananda. 2004. “From ECAFE to ESCAP: Pioneering a Regional Perspective”, in Yves Berthelot ed., Unity and Diversity in Development Ideas, United Nations Intellectual History Project.Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

FUNDS Project. 2010. “Global Perceptions Survey”. Geneva. http://www.FutureUN. org.

Ghani, Ashraf and Clare Lockhart. 2008. Fixing Failed States: A Framework for Rebuilding a Fractured World. Oxford university Press.

Keenleyside, Hugh L. 1966. International Aid: A Summary. New York: Heinemann. Keohane, Robert O. 1984. After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

Mearsheimer, John J. 2001. The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: Norton.

Mitrany, David. 1966. A Working Peace System. Chicago: Quadrangle

Morgan, Peter. 2002. “Technical Assistance: Correcting the Precedents”, UNDP Development Policy Journal, Volume 2, December, 1-22.

Murphy, Craig N. 1994. International Organization and Industrial Change. Cambridge UK: Polity Press.

Murphy, Craig N. 2006. The United Nations Development Programme: A Better Way? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Murphy, Craig N. 2009. The International Organization for Standardization: Global Governance through Voluntary Consensus. London: Routledge Nashat, Mahyar. 1978. National Interests and Bureaucracy versus Foreign Aid.

Geneva: Tribune Editions.

Rist, Gilbert. 1997. A History of Development. New York: Zed Books.

Rittberger, Volker and Bernhard Zangl. 2006. International Organization: Polity, Politics and Policies. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Stokke, Olav. 2009. The UN and Development: from Aid to Cooperation, UN Intellectual History Project. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Toye, John and Richard Toye. 2004. The UN and Global Political Economy: Trade, Finance and Development, UN Intellectual History Project. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

United Nations. 2007. Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel on UN System-wide Coherence, Delivering as One, New York: UN. UN sales number E.07.1.8.

United Nations. 2010. Analysis of the Funding of Operational Activities for Development of the United Nations System for 2008. ECOSOC, document number E/2010/76.

Wendt, A. 1992. “Anarchy Is What States Make of It: The Social Construction of Power Politics”, International Organization (46).

End Notes

- The valuable comments of Craig N. Murphy and Leelananda de Silva on earlier drafts of this paper are gratefully acknowledged.

- Through their Codex Alimentarius.

- After the War, the first UNDP Resident Representative did not arrive in China until 1989.

- The ongoing discussions in the Commission on the fate of the Xayaburi high dam in Laos are a testament to its importance.

- The programme has also received the explicit endorsement of the (Korean) UN Secretary-General.